As part of the Critical Zones exhibition in ZKM Karlsruhe, Hanna Jurisch and I offered workshops to experience the Critical Zone in a more direct way. We called it “Kritische Zone riechen und sehen”, or, translated, “Seeing and smelling the Critical Zone”.

The Critical Zone is all about the processes of living, about living organisms and their entanglements. The difficult thing about dealing with the Critical Zone is that our usual mental models that describe the space we live in seem inadequate and insufficient: top-down maps may show geographical features but are frozen in time. Worse yet, they don’t show any chemical, biological, mechanical processes of living, or any living organisms at all for that matter. They capture a specific point of view, not a point of life (point de vue vs. point de vie as Bruno Latour would say). Sure, maps might sometimes show a single tree, but not the other things that make the tree alive – the water level, the rain, the chemical exchange between tree roots and bacterial colonies, the parasites and the birds that hunt them and so on. There is no future nor past in a map, there is no illness, no movement, no birth or death in a map.

It’s not a problem of scale, as it does not change even if we become very local, if we zoom in closely on one specific point. Here an example:

On the left you see the changes to Dubai over a time period of 1984-2016, taken by satellite, looking down on earth from the outside. This is as an extreme example of terraforming and land development, fueled by vanity and the political will to build funny looking shapes into the ocean. And even with this being the extreme example, the timeframe of thirty years is a large one. A casual observer drinking tea in the orbit and looking down on earth would not notice the change brought by our processes of life.

On the right, a flock of common wood pigeons landed in front of my house in Karlsruhe, February 2021. The polar vortex broke in February, covering large parts of US and Europe in ice and snow. The wood pigeons moved from the woods to cities to find a bit more warmth and food. They move as individuals, until they get spooked by an arriving bike driver, and fly away as a flock, as a superorganism.

This slice of life may be human scale, but it still shows just a point of view. The text description above is needed to turn it into a (very limited, admittedly) point of life.

So Hanna and I decided to cast aside the hyper-global medium of maps and hyper-local medium of video, and searched for a new way to get attuned to the processes of living, of all the tiny interwoven actions happening within the Critical Zone. We arrived at similar but distinct approaches.

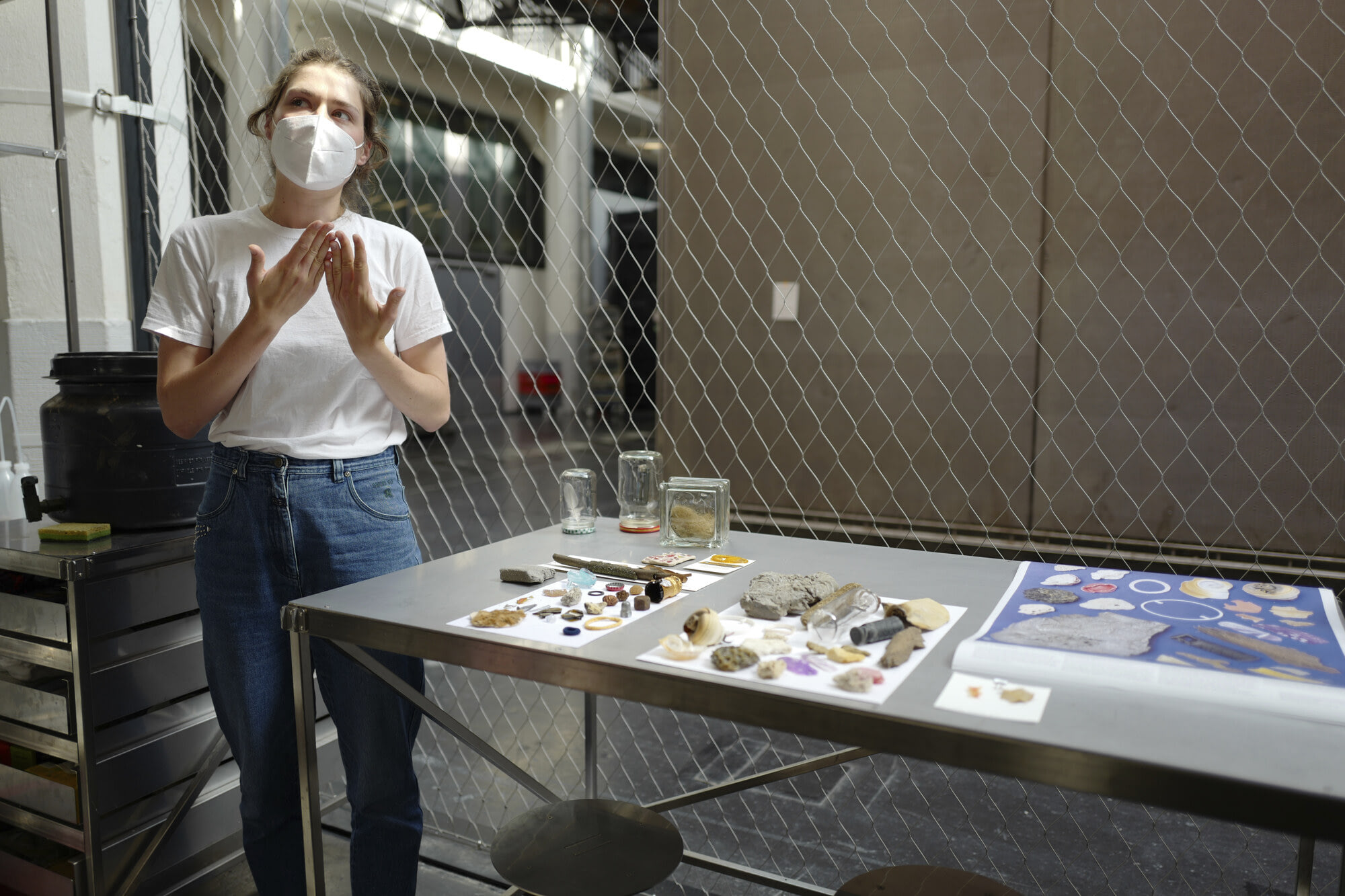

Hanna would take the workshop participants for a walk and let them gather material, human-made and non-human-made alike. Gather everything that grew around the museum or was discarded by people. All the unseen, unintentional objects in the surroundings. Like a dog that sheds hair, processes of life shed bottle caps, pieces of glass, feathers, drinking straws, leaves, bark, empty vodka bottles, screws, scrunchies, moss and concrete.

All the gathered material would later be arranged into sculptures and new taxonomies by the participants.

My own approach was to try and capture the scent of the world around us.

I let participants gather fragrance materials from within their homes – basically everything that has a smell – and use these to create perfumes. Old coffee grounds, earth from a flower pot, fresh leaves, stale bread, or a mushroom found in the garden – all that was welcome, all that we would mix together into a perfume. A perfume of our own – very local – part of the Critical Zone.

I see these perfumes as true ‘scent maps’ of one specific point of life. Not only were the materials gathered by a person who (most of the time) somehow decided to have them in their lives, scents are also seemingly immaterial witnesses of material processes of life. Most smells that surround us are organic in origin, are witnesses of transformation of matter through living organisms, often unseen by us humans. Smell is a process.

One other thing I particularly like about smells is the sensory parallelism. Sure, some particularly smelly molecule might be overpowering others, but most of the times what we perceive as a scent is a combination of many different scents, many different organic molecules stemming from many different processes of life. And we perceive it all at once – something that is impossible to achieve by mapping the Critical Zone in the usual, top-down way.

On the walk with Hanna we would sometimes also pick up fragrance materials, adding the surroundings of the ZKM to the perfumes.

The fragrance materials brought from home often included herbs and leaves, spices, as well as discarded cooking materials.

To extract a fragrance from the materials we would put them into freezer bags and put enough 96% alcohol to cover the contents.

Soaking fragrance materials in alcohol and waiting for some time is the usual process for making tinctures. Of course, we didn’t have the 3-6 weeks that it usually takes, but just the 3 hours of the workshop. To speed things up we used an ultrasonic machine commonly utilized to clean delicate things like jewelry or glasses.

While the machine is far from silent, it is not as loud as it appears in the video – the microphone in the camera is much more sensitive to the high frequencies than the human ear.

The ultrasonic waves create cavitation bubbles in water and alcohol. As these tiny high pressure bubbles collapse, they agitate the liquids and move the fragrance molecules into the solution. A tincture that before would take 3-6 weeks to create now takes just 10-12 minutes.

After running the machine, we filtered the newly formed tinctures to get rid of larger pieces of organic matter.

Filtering (from left to right):

- puffball mushroom, paprika, rotten mushroom, chili sauce, half-dried plantain peel (smelled tasty, of hot chili, a bit like mushroom pizza, but also a bit wet and mossy)

- rosemary, thyme, lavender and peppermint (smelled fresh, of lavender, grassy and a bit oily)

- caraway, lavender, evening primrose seeds, coffee grains, bread (smelled fresh, grassy but also sweet and warm)

We would label the filtered perfumes, and talk about what we think about the smell. Interestingly, even though we used some questionable and uncommon materials, none of the scents could be described as ‘repugnant’ or ‘foul’. Instead, many smelled mossy, grassy, woody or fresh.

Except, perhaps, the one time a participant brought a 100 Kenyan Shilling banknote with them – the lowest denomination and most commonly used note. We did a tincture solely of the note, without mixing it with other ingredients.

The tincture took a while to filter through, and had a very intense metallic, oily, dusty warm smell.

Here are the results of the first batch of Critical Zone perfumes:

Left to right:

- mushroom from near the Städtische Galerie Karlsruhe (smelled earthy)

- puffball mushroom, paprika, rotten mushroom, chili sauce, half-dried plantain peel (smelled tasty, of hot chili, a bit like mushroom pizza, but also a bit wet and mossy)

- mushroom, old sock, unwashed sheep wool, sage (smelled earthy, mossy, warm)*

- banana peel, peanut, peanut husk, mint, blackberry and blackberry leaves (smelled a bit fruity, grassy and tart)

- caraway, lavender, evening primrose seeds, coffee grains, bread (smelled fresh, grassy but also sweet and warm)*

- bovist mushroom, bolete mushroom, straw, dry grass, various branches (smelled earthy, mushroomy, spicy)

- sheep wool, lavender, mint (smelled of sweaty lavender)*

- sawdust, white lichen, dry leaves, grass (smelled woody and a bit of olive oil)*

- rosemary, thyme, lavender and peppermint (smelled fresh, of lavender, grassy and a bit oily)*

- rosemary, lavender, dried linden leaves, street jasmine, fir branch (dark, smooth, coniferous)

- spirulina (intense algae smell)

*interesting scent, should try again!

With this process we captured the scents around us and moved them onto one point, into one bottle. What was before atmospheric, nebulous, became concentrated and focused. Which goes, perhaps, counter our notion that the unfocused, atmospheric, the background should be just as valuable as the focused, clearly defined, the foreground.

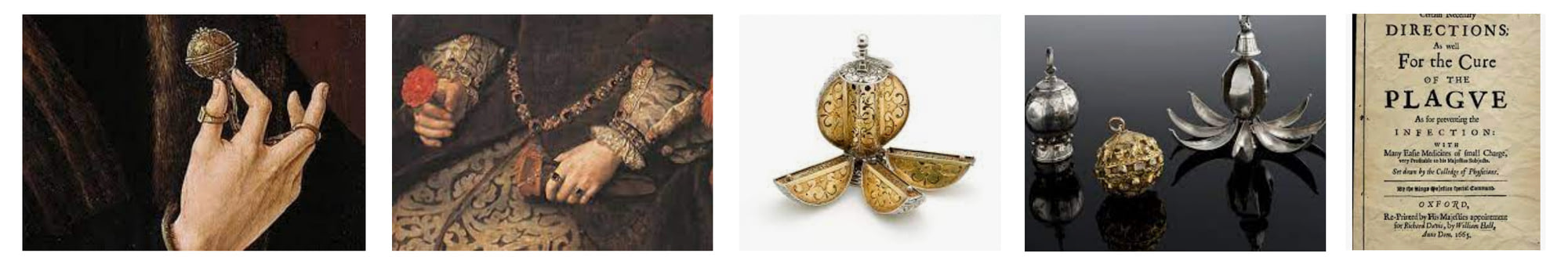

I thought of using a nebulizer to spread the perfume back into open space, but instead got inspiration from another source: the pomanders and the long-beaked pestilence masks of the Middle Ages, which used to house herbs and perfumes, intended to protect the doctor from the bad smells (at the time thought to cause the illnesses).

As we were wearing masks at the time (the future reader probably remembers that there was once a pandemic when we had to wear masks indoors), we felt disconnected from the scents in our surroundings through the thin cloths of these masks covering our noses.

So, we decided to invert the experience: to put the extracted scents of our surroundings onto our masks, allowing us to perceive the smell of the surroundings again.

And so we went full circle, from not consciously perceiving the smells and associated processes around us, to isolating and focusing on them, to bringing them back to the periphery of our senses.

The Critical Zone is hard to map. Processes of life are disjointed in time and space. Organisms turn out to be holobionts, assemblages of multiple other organisms for which the host is the territory. A simple task to list all the things one organism depends upon explodes into describing half the world – since if I’m dependent on bread from a bakery, I’m also dependent on the well-being of the bakers and so on and so forth.

I was quite discontent with the beautiful bottles of colorful liquids that were created. They seemed too beautiful, too precise, just one more of those things that are created to describe something but end up being a thing in itself.

I suspect, it has something to do with our senses. Our eyes focus on just one thing, and everything we create for our eyes ends up being in focus, ends up offering only one point of view at a time, covering up other things behind it. There is no simultaneity possible if we remain focused on one thing.

And perhaps, there’s quite enough things out there that let us focus on just one thing. Enough visual media, enough displays, diagrams and films. Enough.

Perhaps it’s time to start describing processes in a medium that allows for their complexity. Like sound. Like movement and proprioception. Like putting the extracted perfumes on our masks and forgetting about them. Let’s allow ourselves to listen to the peripheral, the background, the ephemeral.

Let’s give ourselves time to smell the Critical Zone.