This is a translation of the German version of the essay, published in 2017

The lens through which we experience the world shapes the language that we use to describe it.

The linguist Sarah Thomason writes about Montana Salish, a language spoken by about a hundred people in the Spokane Indian reservation:

The word they use for automobile means “that it has wrinkled feet,” [..] If you’re a tracker, you’re going to be noticing the tire tracks — the focus of that particular word.

And the word for telephone means “you whisper into it.”

Using the description of the physical effect of an object as a designation for this object is not unique. After all, in German we also say Fernseher (one who sees far) for television or, less frequently, Fernsprecher (one who speaks far) for the telephone. Here the language indicates how the technical solutions extend, and – perhaps – replace our senses.

In Understanding Media, media theorist Marshall McLuhan describes the development of media and its relationship to the human body:

Any invention or technology is an extension or self-amputation of our physical bodies, and such extension also demands new ratios or new equilibriums among the other organs and extensions of the body. (p. 55)

With unending technological progress, the equilibrium between the body and its extensions must therefore be constantly renegotiated.

Since McLuhan wrote his work in 1964, whole new generations of media have evolved from the radio, television, telephone, and telegraph to which he referred. How are these media shaping our bodies?

To answer this question, I’ve explored the relationship of the body to the medium in a variety of themes:

- Object and relation

- Speaking to the machine

- The loss of handedness

- The constriction of vision

- Bodily expressivity

- Mental gymnastics

- Self-movement

- Breath and rhythm

- Body politics and

- The warmth of the machines

Object and relation

The philosopher Peter Sloterdijk describes in his Spheres the primal state of a togetherness, a wholeness that the unborn human being experiences in its connection with the placenta. The placenta belongs neither to the child nor to the mother, but provides the child with everything it needs.

While in some cultures the placenta and umbilical cord are ritually buried or made into necklaces to be worn after birth as a sign of the continuing connection, in the western world the artefacts of birth are not honoured. So the human being is torn from its first primordial sphere without being given a replacement. Until it gets its first smartphone.

A smartphone is a flat object made of metal, plastic and glass, usually slightly smaller than a human placenta. You carry the smartphone around with you, you caress the smooth, cold glass surface with your fingers, and in return the smartphone connects you to the outside world, promises safety (in case something happens) and social capital (in case something happens, you can film it). Like the placenta, it satisfies the most basic needs, like the placenta, it is always there between you and the world, like the placenta, it is not the form that matters but the content - the validation and attention of the well meaning counterpart. Who doesn’t remember gazing thoughtlessly at a blank screen several times, waiting for a notification, waiting for the sign of being remembered, seen, recognized.

In this relationship, the smartphone assumes the position of an outsourced organ that stands between the user and the world, and is neither fully attributable to the user nor to the world. Not surprisingly, this leads to increased smartphone use among people with weak internal locus of control, i.e. people who do not feel in control of the events in their lives.

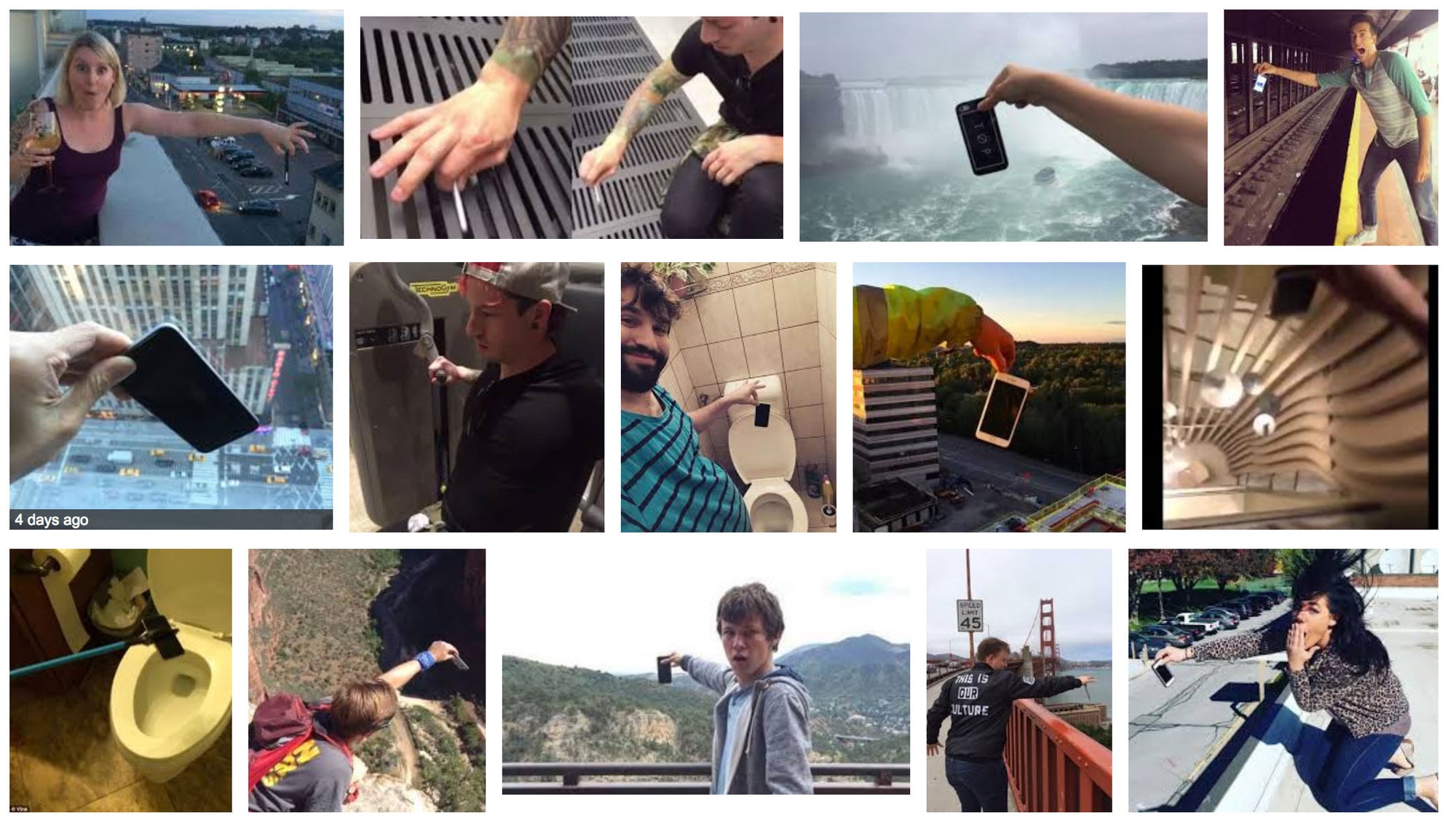

The relationship is so meaningful that people want to keep using their smartphone even when the screen is broken. It is hard to think of another example of people lovingly running their fingers over shards of glass. Extreme phone pinching has also gone viral as a dare. This involves holding a smartphone with two fingers over a source of danger, risking a fall into water or from a great height. The danger to external organs provides a real thrill - almost as strong as putting yourself in danger.

Speaking to the machine

In addition to the touch interface, you can also communicate with the electronic placenta via voice. Since Siri appeared on iOS devices in 2011, nearly all smartphones try to get you to speak to them.

Voice input is heralded as the next big breakthrough, and indeed allows complex commands to be constructed in a single block.

But what happens to our voice when we speak to a machine?

A human being you talk to can give you feedback in the middle of a sentence, through facial expressions, gestures or speech. The machine can’t yet; it acts like an opaque, magical black box that doesn’t reveal its thought process. Its ability to understand what you mean is growing every day, and yet you must first learn how exactly to express your needs and wants to the machine. The discoverability of voice interfaces is severely lacking.

Another limitation of speech input is the actual speech recognition. To be properly understood, you need to speak clearly, slowly and without an accent or dialect. Preferably in a quiet environment.

The voice is a social tool and the social relationship between the parties determines the tonality, loudness and clarity of the voice. You may need to speak clearly, loudly and dialect-free when talking to an elderly relative or appearing in court. However, the technical shortcomings of text-to-speech interfaces enforce the same attitude, the same demeanour, when talking to the machine. If you are not polite to your smartphone, you will be ignored.

The loss of handedness

There are several theories as to why most people are not ambidextrous but have a dominant hand. One of these is called Asymmetric Division of Labor in Human Skilled Bimanual Action and states that in ambidextrous work, the tasks of the hands often differ: while the dominant hand performs fine movements, the non-dominant hand assists by holding or readjusting. This specialization creates advantages that lead to a preferred handedness over time.

The last remaining computer interface for which the fine motor skills of the dominant hand are relevant is probably the mouse or trackpad. There was a period in the development of mobile devices - from the late 1990s to the first iPhone in 2007 - where the touch interface existed, but was not operable without a stylus. The iPhone, with its lack of additional input devices, lost some of the functionality that was present in PocketPC and Palm Pilots (handwriting recognition!), but dominated the market and redefined the paradigm of mobile interfaces.

Small, lightweight devices with a touch interface whose work surface matches the display surface do not require specialization of the hands. A smartphone can be held and operated with one hand. Larger tablets can be held with both hands and operated with both, since the interfaces are quite error-tolerant.

The current development again shows a trend towards hybridization of interfaces: Microsoft Surface Pro has a touch interface, a stylus and a hardware keyboard; Apple’s iPod Pro has a stylus and Microsoft Surface Studio as well as Dell Canvas combine pen, touch and input via hardware dials with large displays.

Although fine motor input with a mouse or pen is still essential for certain tasks, the need for hand specialization seems to be diminishing. Whether this leads to measurable differences in handedness and its expression remains to be seen.

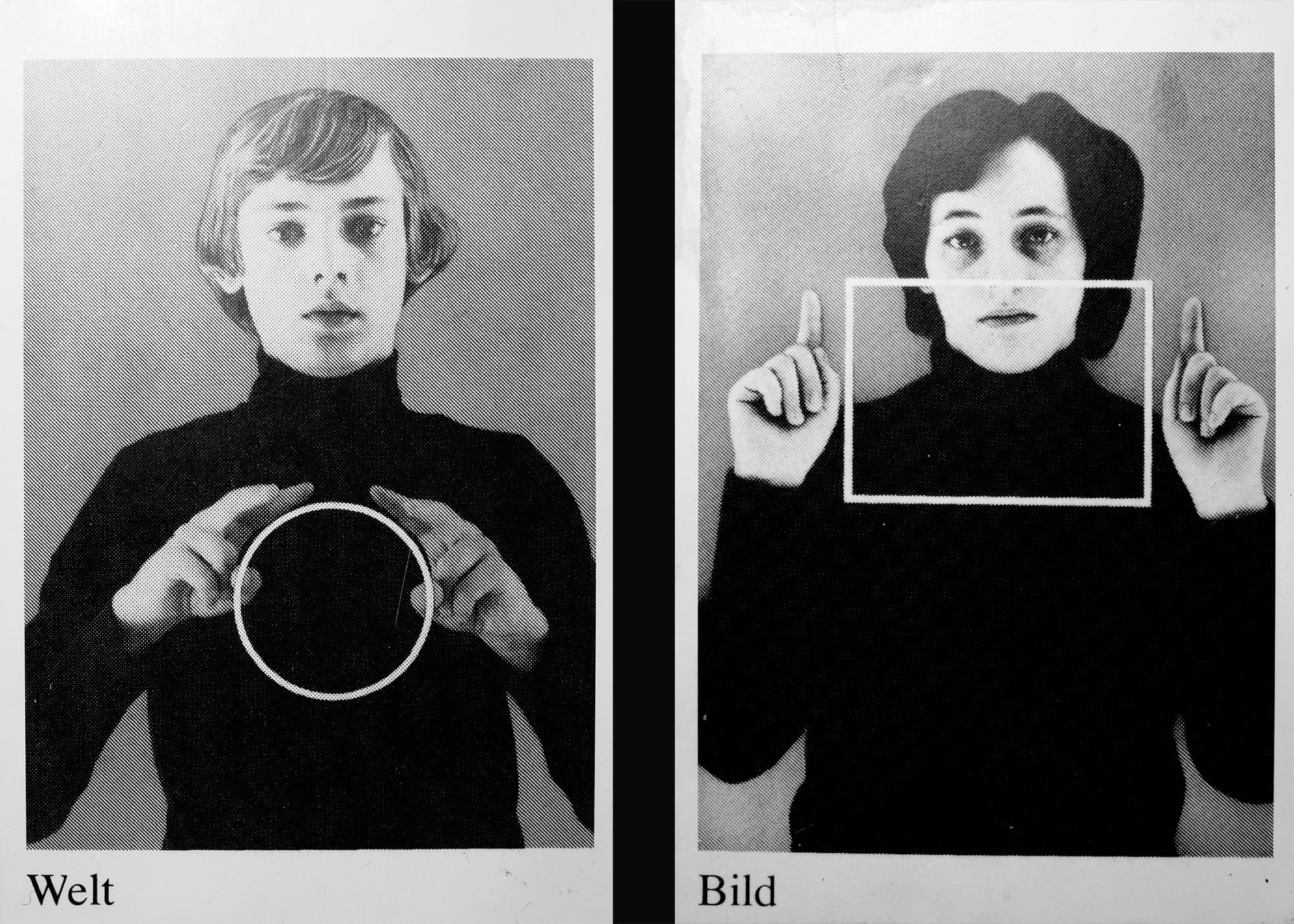

The constriction of vision

The screens around us typically have a viewing angle of 25 to 30 degrees. Sure, there are giant displays and tiny screens, but because the viewing distance varies, the viewing angle remains mostly the same. One exception might be movie theaters, where THX recommends that the viewing angle of the screen be no less than 40 degrees.

Regardless of the size of the screen, when we are free to position the screen, we place it directly in front of us. This makes sense: with the screen directly in front of us (and slightly lower than eye level), our eyes move the least. More than in any “real world” interaction, our gaze is directed forward, moving lazily within a predefined bounding box that occupies a fraction of our field of vision. We don’t look around corners, near or far-there’s simply nothing there that would interest us. Our technology choreographs our eyes into an extremely boring waltz within the confines of the screen prison yard.

It wouldn’t be so bad if there weren’t an apparent connection between eye movement and the psyche.

One study showed that people with affective disorders have a lower saccade rate (rate of rapid movement of the eyes between fixation points) than in general population.

In Eye movement analysis for depression detection, the (decreased) rate of eye movement has been used to diagnose depression, with 70-75% accuracy. Even more, there exists a therapy called Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) that is used to treat depression. This form of therapy follows the AIP (adaptive information processing) model, which states that unprocessed and dysfunctionally stored memories can serve as a source for mental disorders such as PTSD, anxiety disorders, and depression. These memories now need to be brought into short-term memory and processed, and EMDR accomplishes this through lateral eye movements prompted by the therapist during the session, which are designed to promote the storage of memories.

One study on EMDR found a significantly higher success rate with usual treatment supported by EMDR than with usual treatment alone. A meta-analysis of the studies confirmed the link between eye movements and emotional memory processing.

An exercise in Stanley Rosenberg’s book Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve uses eye movement as part of a relaxation technique:

- Lie on your back

- Interlace the fingers of your hands and place them behind your head

- Without turning your head, look to the right

- Remain there until you spontaneously yawn or swallow

- Return to the neutral state with head and eyes straight

- Repeat on the other side

In my limited experience this exercise produces an almost immediate physical response, and makes me yawn within seconds.

Another exercise is to widen your gaze in order to calm the autonomic nervous system. Try to create the opposite of tunnel vision, the opposite of a laser-sharp focus, relax and widen your gaze, and in just a few seconds you may find yourself calmer, less angry and less anxious. [I have a pet theory that photography (as a hobby) is so popular precisely because it allows the photographers to modulate, to widen their gaze.]

All of this research is very new and very exciting - it may indeed turn out that simple eye movements can modulate memory processing and have an impact on the autonomic nervous system. It also forces us to consider how we have limited our eye movement by fixating so much on screens - screens that move the world around us but hardly our eyes.

Bodily expressivity

It’s not easy to convey tone in textual communication. A period at the end of a text message might be interpreted as anger. A lack of emoticons might be perceived as rude. At the same time, these signs the kind of bodily expressiveness one would expect in a real-world conversation. You do not laugh out loud when you write lol, and you do not necessarily smile when you attach a smiley to a message.

When using modern technical devices such as smartphones or PCs for communication, one’s own physical expressiveness becomes unnecessary, since it is not captured by the machine and does not reach the recipient. The interface of the devices is two-dimensional and can only be operated with minimal finger movements. Physical expression is also reduced to these finger movements.

As a result, regardless whether we are writing a friendly message, a letter of complaint or a declaration of love, the body assumes the same position and performs the same movements.

It is the same on the receiving end: since the physical reaction is not transmitted, it tends to be neglected - after all, it is not socially acceptable to shout at or kiss your cell phone.

Thanks to our outsourced electronic organs, all the different emotions conveyed by the messages we send emerge from one rigid motionless body and arrive in an equally rigid motionless body.

A medium of communication that involves the body more is sign language. Sign languages are not derived from spoken languages, but are languages in their own right. The meaningless units (phonemes) are combined into meaningful semantic units. The characteristics of this combination - sequence, hand shape, hand position, range of execution, and movement execution - determine the content of the message. Much more than spoken languages, sign languages can convey the message simultaneously through multiple pathways because they employ the full expressive power of the body and body movements in three spatial dimensions.

Among humans, sign language is not widespread, is not universal, and has many variations and dialects. An interesting exception was Martha’s Vineyard an island near Boston: due to hereditary deafness, four percent of the population was deaf in 1850, and so the entire population had developed and spoke their own sign language.

Sign languages could perhaps become more common again in the future - a team of students from MIT has developed SignAloud: Gloves that convert ASL (American Sign Language) into spoken words.

Mental gymnastics

A 2014 study showed that just thinking about physical processes activates muscles. In the study, wrist muscles were first weakened by immobilization. One group was then asked to do daily exercises on these muscles – in their imagination. This group had 50% lower loss of strength compared to the control group that did no mental exercises.

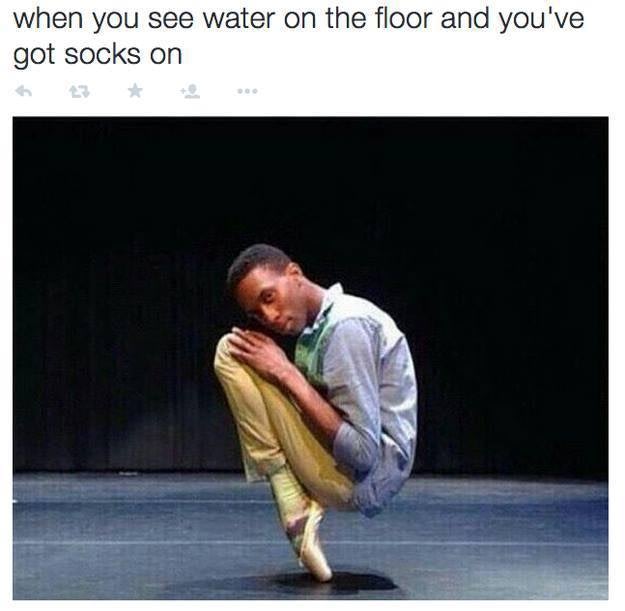

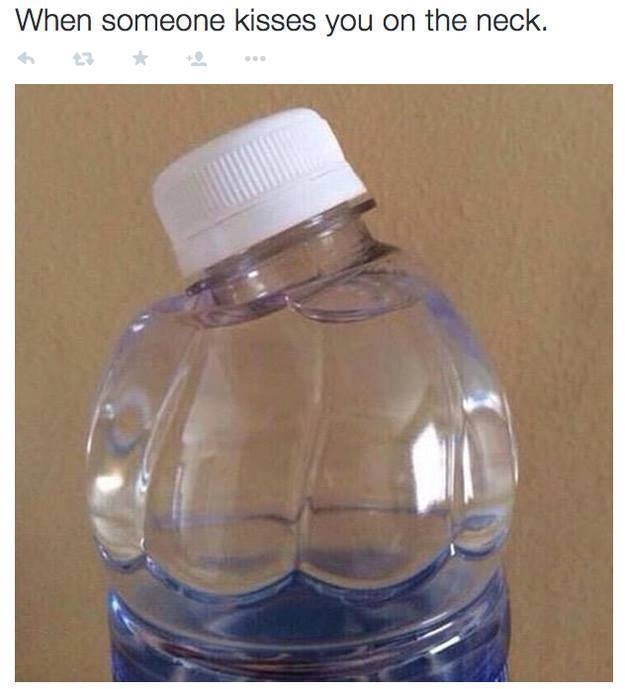

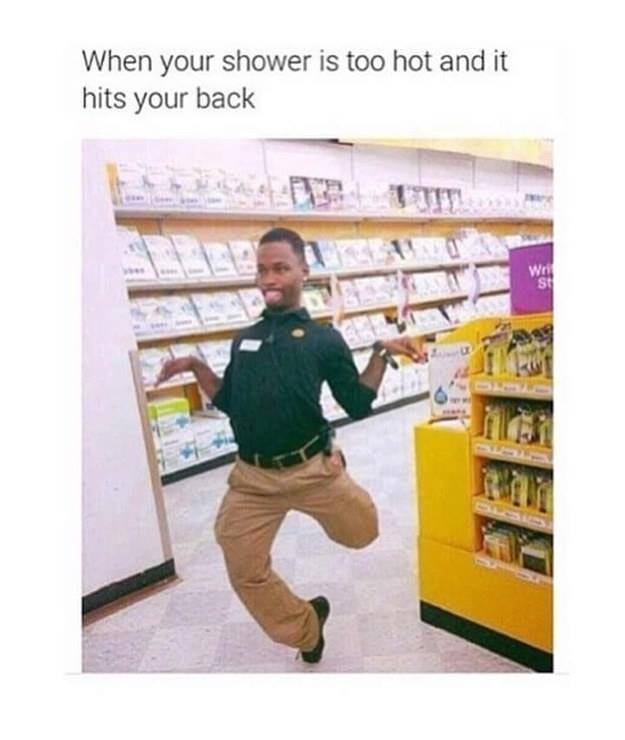

The memes that spread across social networks have many different themes. Most respond to current events or mimic social situations. One of the themes could be summarized under the title “Do you remember the feeling when…”:

These memes show the situation of a specific bodily experience. If we extrapolate the results of the aforementioned study, viewers actually feel a weaker version of the experience when they see these images.

In a screen-filled everyday life with insufficient richness of bodily experiences, these memes can have a powerful effect. When the memes are shared, their inherent choreography is performed, perhaps as a worldwide, simultaneous, location-shifted hunch of the shoulders – simply because everyone imagined being kissed on the neck.

A a similar meme category actually tries to choreographs you:

Self-movement

Most of the objects around us were developed with an idea of a human body that is still. A body that lacks self-movement. In these design considerations the body of the user only moves when intended, never failing to correctly execute the movements. The myriad of unintentional, involuntary self-movements of the body such as stretching, automatic change of position, yawning, sneezing, breathing, trembling, etc. are not taken into account in product design considerations.

Stimming - an English term for involuntary self-stimulation of the senses, is most often used in reference to people with autism. But it also includes such commonly used movement patterns as tapping one’s foot, humming, or fidgeting with small objects. The function of stimming, as Ask an autistic explains to us, is threefold: it serves as self-regulation in the face of overwhelming sensory input, as sensory enjoyment, and as self-expression.

Not only are all forms of stimming suppressed out by parenting and school systems - most work environments are stimming-unfriendly: perhaps you have to be quiet and sit still for social reasons, or perhaps the objects around you can’t be fidgeted with. There are manufacturers of stimming-friendly jewelry and toys, such as All Things Sensory, that offer special objects to chew, stretch, twist, and feel.

Electronic devices like laptops and smartphones are decidedly unsuitable for stimming – they tend to be quite expensive, made of metal and glass, and they break easily. Instead, stimming is done digitally – by moving the mouse cursor aimlessly, by needlessly clicking or selecting whole passages of text.

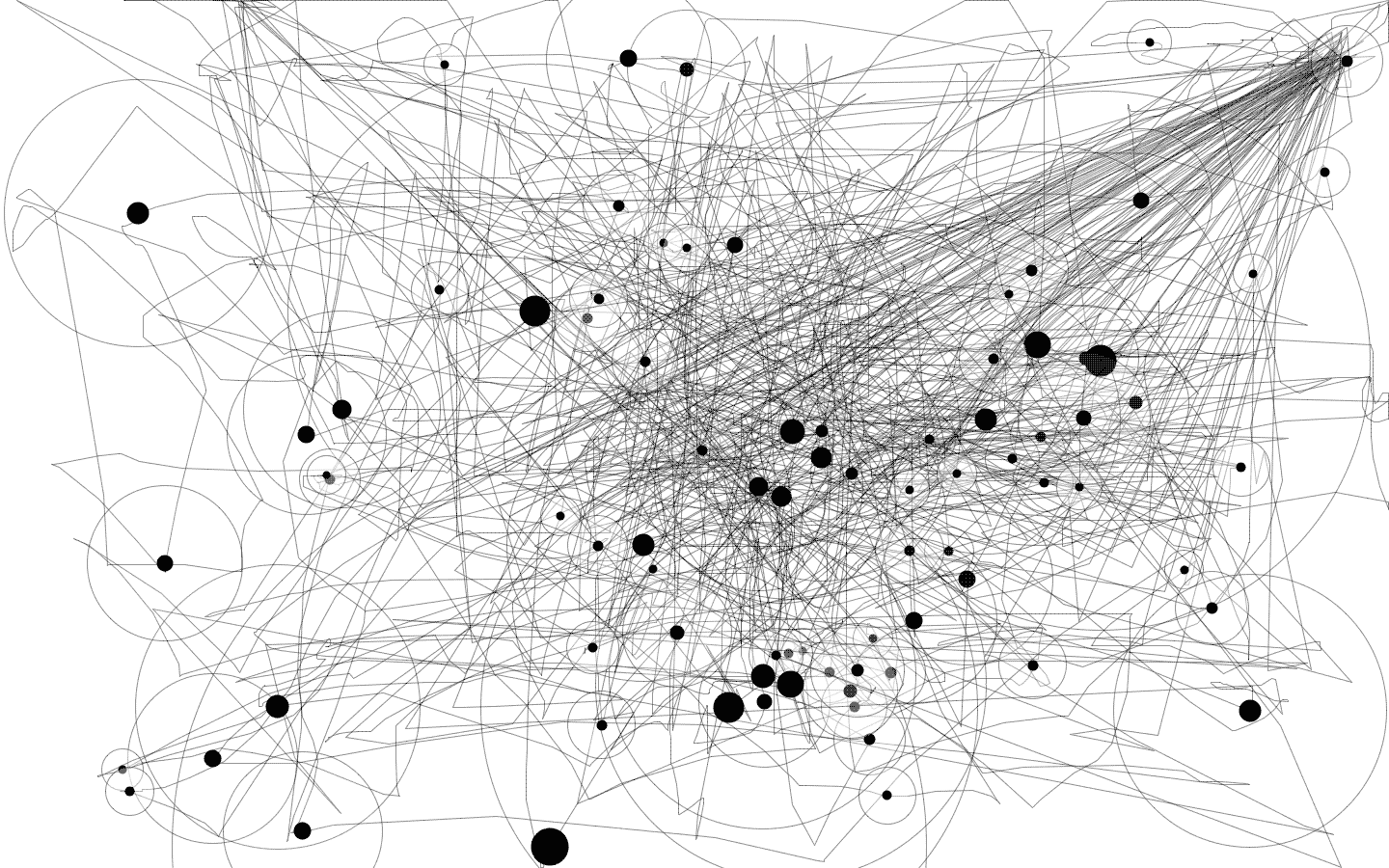

A small app called IOGraphica helps to visualize the mouse movements. With it, you can better study the daily mouse pointer run and enjoy abstract painting as a side result of your own work.

I’ve been exploring the topic of self-movement in Terra Trema – a photographic collaboration between the photographer’s hands and the iPhone’s panorama-generating algorithm. To create a panorama with an iPhone, you have to make a movement, you have to slowly and carefully rotate the phone along the x-axis. No matter how steady your hands appear to be, the movement is imperfect, and the algorithm tries its best to hide these imperfections and produce plausible-looking results. Only when the images are superimposed does the trembling of the hand become apparent.

Breath and rhythm

Our post-industrial society has very few signals that would give us a perceptable rhythm. The hunter-gatherers had continuous walking; agriculture, crafts, and factory work were structured by repetitive motion. Sitting, standing, or lying in front of a screen does not involve rhythm.

With a set rhythm, there is less to choose from. It is an external process to which one can attach oneself, and be carried by it like by a wave. Rhythm-giving work songs existed in all cultures - they made the long, hard work more bearable.

The 1966 documentary, Afro-American work songs in a Texas prison shows work songs in action:

The tradition of work songs has completely disappeared in the post-industrial world. Nevertheless, music is often used as a sustaining, rhythm-giving element. NYTimes reports positively about music in the workplace:

People’s minds tend to wander, “and we know that a wandering mind is unhappy,” Dr. Sood said. “Most of that time, we are focusing on the imperfections of life.” Music can bring us back to the present moment.

In a study on respiratory rhythms, it was shown that the brain regions amygdala (responsible for the fear response, among other things) and hippocampus are activated differently during inhalation and exhalation. These regions are activated much more strongly during inhalation through the nose than during the phase of exhalation. Thus, the reaction time of the test subjects who were supposed to recognize a frightened face was significantly shorter during inhalation. The rhythm of breathing apparently may have an influence on our perception.

These findings may explain the calming effect of activities that focus on breathing, such as jogging, meditation or yoga. The popularity of these practices is growing, and the reason may be that our work process lacks activities that dictate the rhythm of breathing and movement.

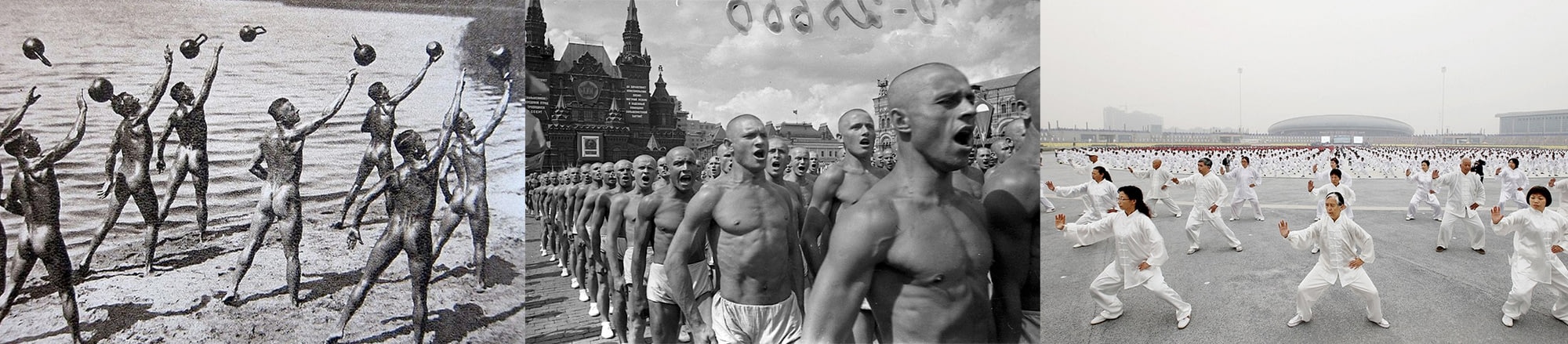

Body politics

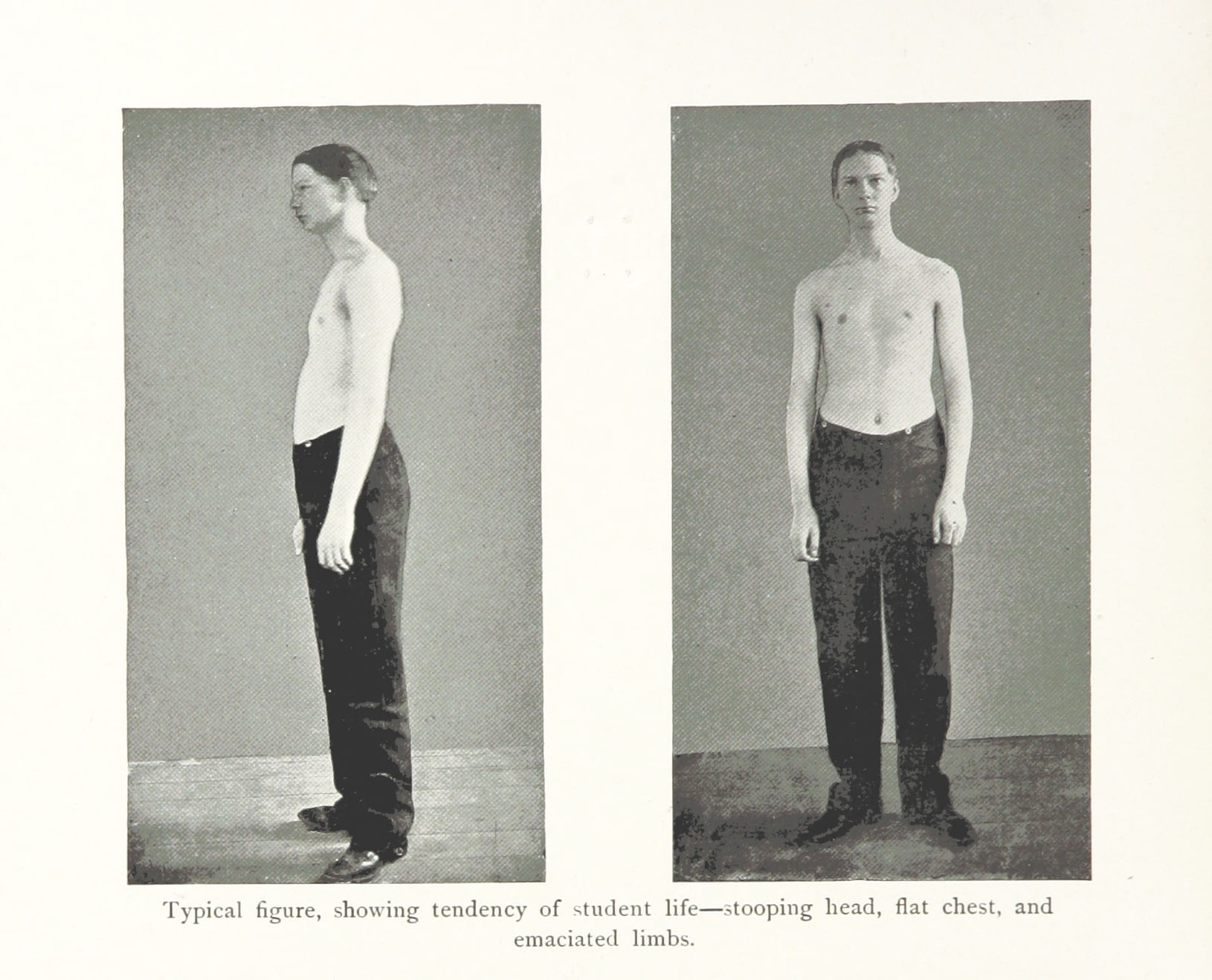

The great ideologies of the twentieth century claimed the power to shape citizens’ bodies. The body had to conform to a clearly defined ideal of fitness and appearance.

In societies with collectivist values, such as Japan or China, these norms still apply. In 2008, for example, Japan passed a law requiring the waist circumference of all citizens over the age of 40 to be measured annually, with penalties for communities and businesses whose residents and workers are overweight.

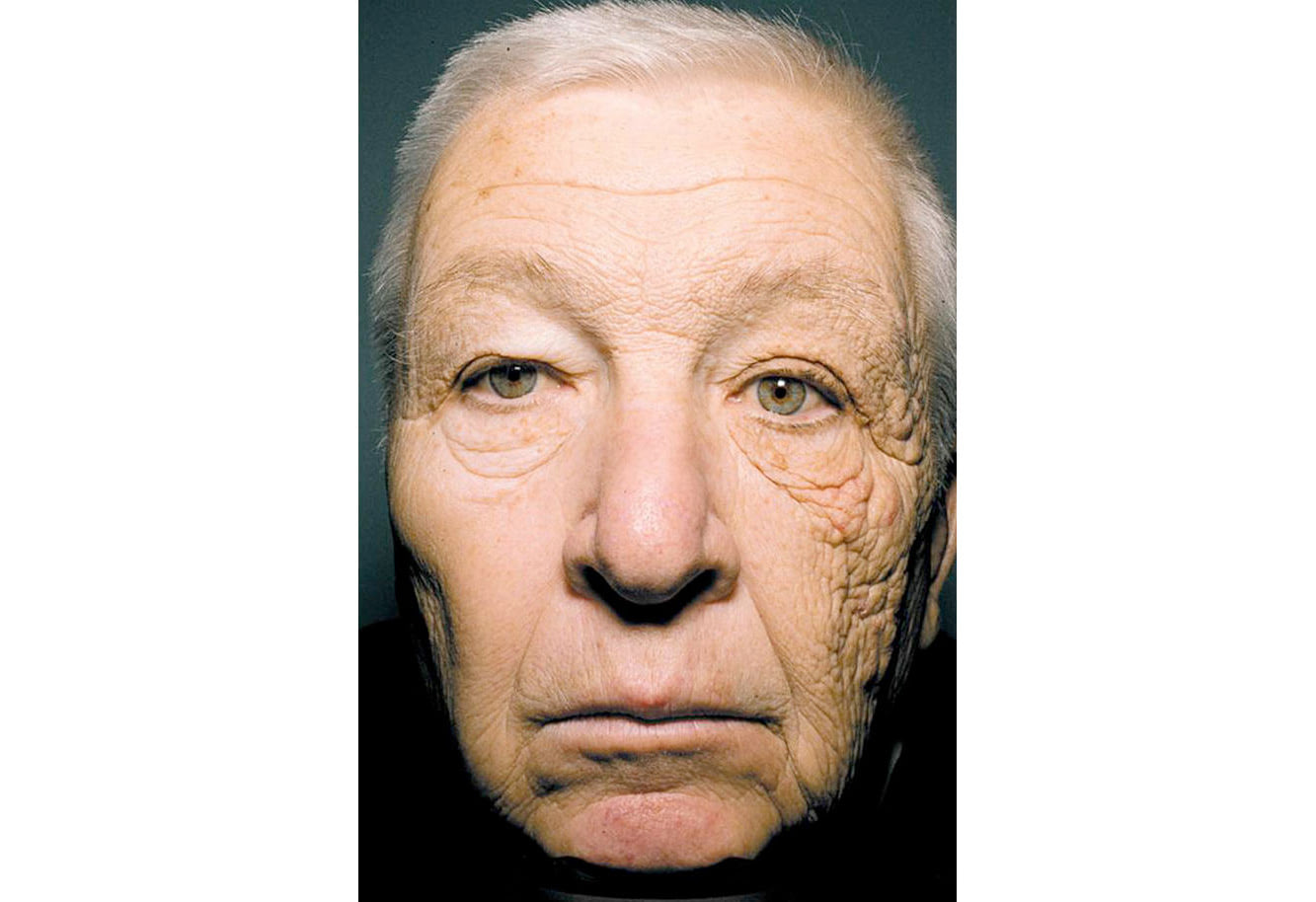

Post-industrial Western society does not put direct pressure on the body. But there are other forces that do. Just as the ownership of the means of production determines power relations, the use of the means of production determines the shape of our bodies. The movement patterns of taxi drivers, teachers, architects, salespeople, factory workers and managers are different. They use different muscles, adopt different postures, and after years of employment this external pressure on their bodies becomes visible.

However, this difference has been diminishing for years: more and more heavy physical labour is being automated, and more and more of the same body extensions - such as laptops or smartphones - are being used in a wide variety of occupations. As the body extensions used in occupations become more similar, so do the bodies.

Even in the absence of direct political influence, the total use of technological body extensions leads to the homogenization of bodies.

The warmth of the machines

For all the mechanical coldness of the machines, for all their austere, meticulously designed minimalism, they still surround us with warmth. They radiate the warmth of discharging batteries, the warmth of stressed chips. They show us that they are there for us - calculating, executing, processing. We understand this heat and the noise of the fans. We’ve given the machine a job to do, and now it’s doing it.

It is probably the most underestimated subtle signal a machine can send.

Warmth is such an animalistic quality that it’s hard not to see the machines as alive, less alive when they’re off and more alive when they’re working, calculating, trying to solve the task we’ve given them. The body of the machine gets warm, vibrates with inner movement, comes alive in those moments.

As computer chips become more and more power efficient, the subtle signals of machines at work – the whine of the fans and the warmth of the body of the machine – begin to disappear. This disappearance is not only a loss of interactive feedback (however unplanned that feedback was), but also a loss of the machine as a body.

Cloud computing is another trend that limits the expressiveness of computer bodies. As more and more computing power moves to centralized data centers, the physical expressivity of consumer devices diminishes because they become thin clients: their computation is externalized to the cloud and so they generate less heat. Instead, the heat that would be theirs is captured in large, industrialized server farms. Far from green pastures, they are made up of noisy, windowless sheds, and the warmth of the server body kept in the narrowest server rack won’t warm you.

In conclusion

McLuhan writes:

Physiologically, man in the normal use of technology (or his variously extended body) is perpetually modified by it and in turn finds ever new ways of modifying his technology. Man becomes, as it were, the sex organs of the machine world, as the bee of the plant world, enabling it to fecundate and to evolve ever new forms. (S. 57)

Man and machine change each other as they extend each other. So what is the current state of our bodies in the symbiotic relationship with the machine world?

Our past, our memory, our voices and our connections, our sense of place and our safety are externalized to the machine. We must speak politely and clearly to be understood. We move less and our movements are less complex. We don’t even move our eyes properly, and the physical expressiveness that used to be an important part of communication has been outsourced to the expressiveness of the machine. Our world does not structure our bodily movements as it used to, the bodily interaction is less rich, less pronounced and leaves us with the feeling that something is amiss.

It doesn’t have to be this way. We can design our interactions, our environment in a way that does not simply extend (and extinguishes) our bodily functions. We can design them in a way that lets the body play, lets the body have the place and the rich experiences that it needs. The choreography of everyday life, instead of becoming dull and boring, could become exciting and enriching.