My father has studied electrical engineering in the seventies and likes to tell the story how he approached a famous soviet neuroscientist, asking him for an opportunity to work in brain research. He had this idea, says my father, that science should be able to read and decode a human brain, effectively granting humans immortality. It could be easily done from the electrotechnical point of view. “Young man, we don’t do this kind of things here” he recalls the professor saying. He smiles at the memory, as he is now of the opinion that it is not the duty of science to grant immortality. For that, he believes, other mechanisms are in place.

My father went on to work at the Pavlov Institute of Physiology, placing electrodes in dog’s stomachs and graphing the response to different stimuli. I recall visiting him there as a child in the early 90s and playing Alley Cat and Silent service, a submarine simulator, on the institute’s computers.

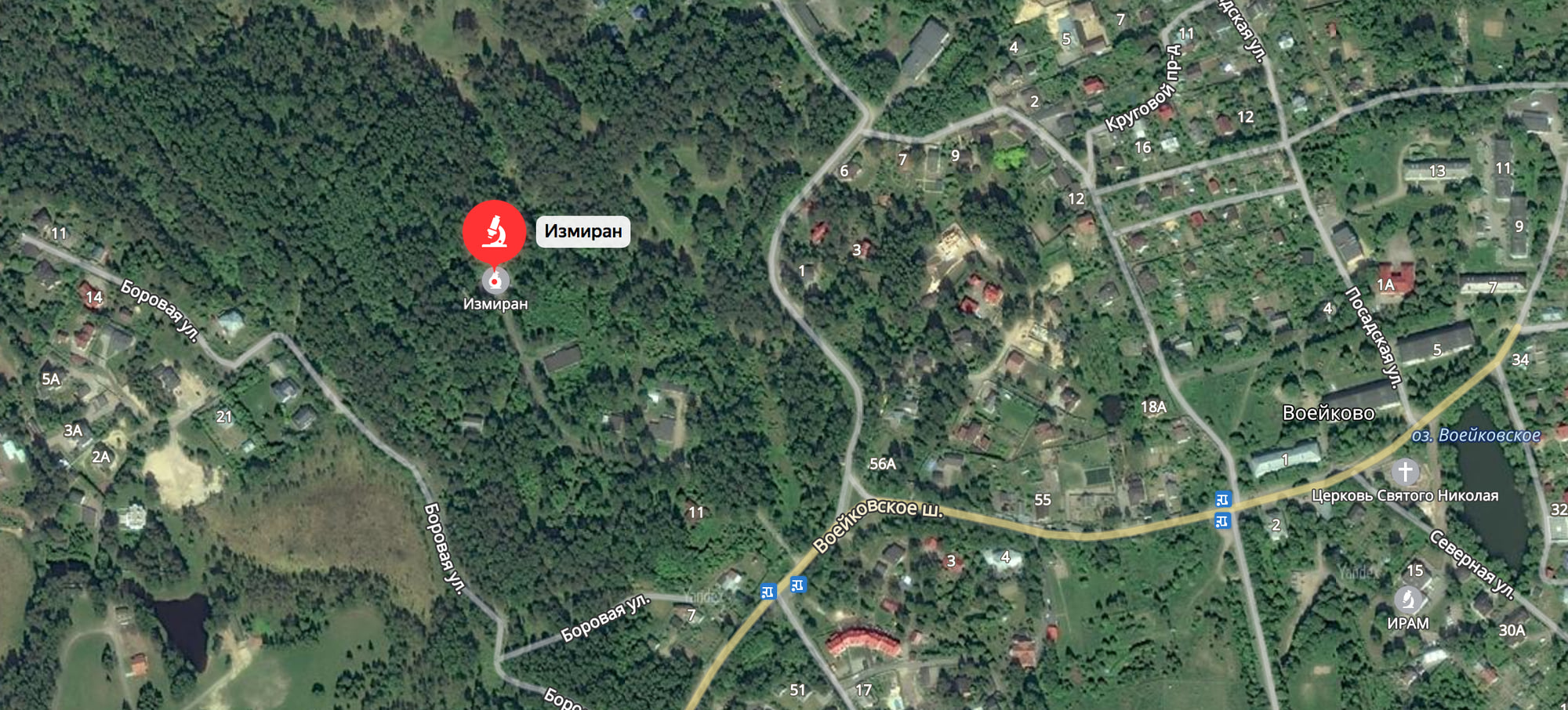

The Pavlov Institute lies a bit outside of St. Petersburg, in a village called Koltushi. Right next to the village the picturesque Koltushi heights lie. They were formed by the last ice age and a few thousand years later were declared UNESCO world heritage. Just behind these hills lies the village of Voejkovo, named after the Russian explorer and climatologist Alexander Voejkov. In the sixties, the Institute of Terrestrial Magnetism, Ionosphere and Radiowave Propagation built a magnetic ionospheric observatory there. It would become the second workplace of my father.

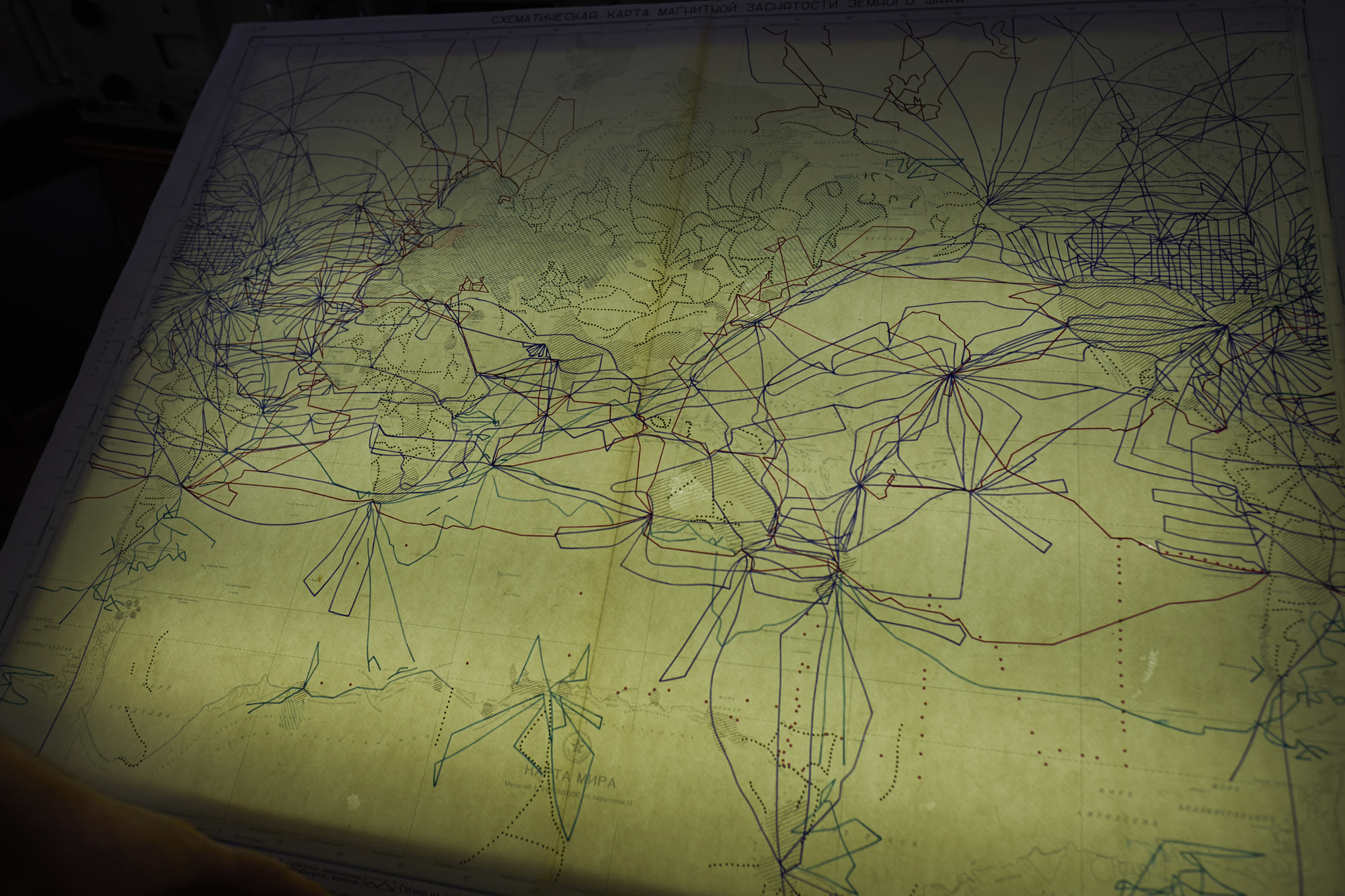

The mission of the magnetic ionospheric observatory is to take local measurements of the fluctuations of the earth magnetic field and the depth and composition of outermost atmospheric layer, the ionosphere, which starts at around 80 kilometers above ground. Do these fluctuations affect life on earth? Other scientists are researching it - the observatory just observes.

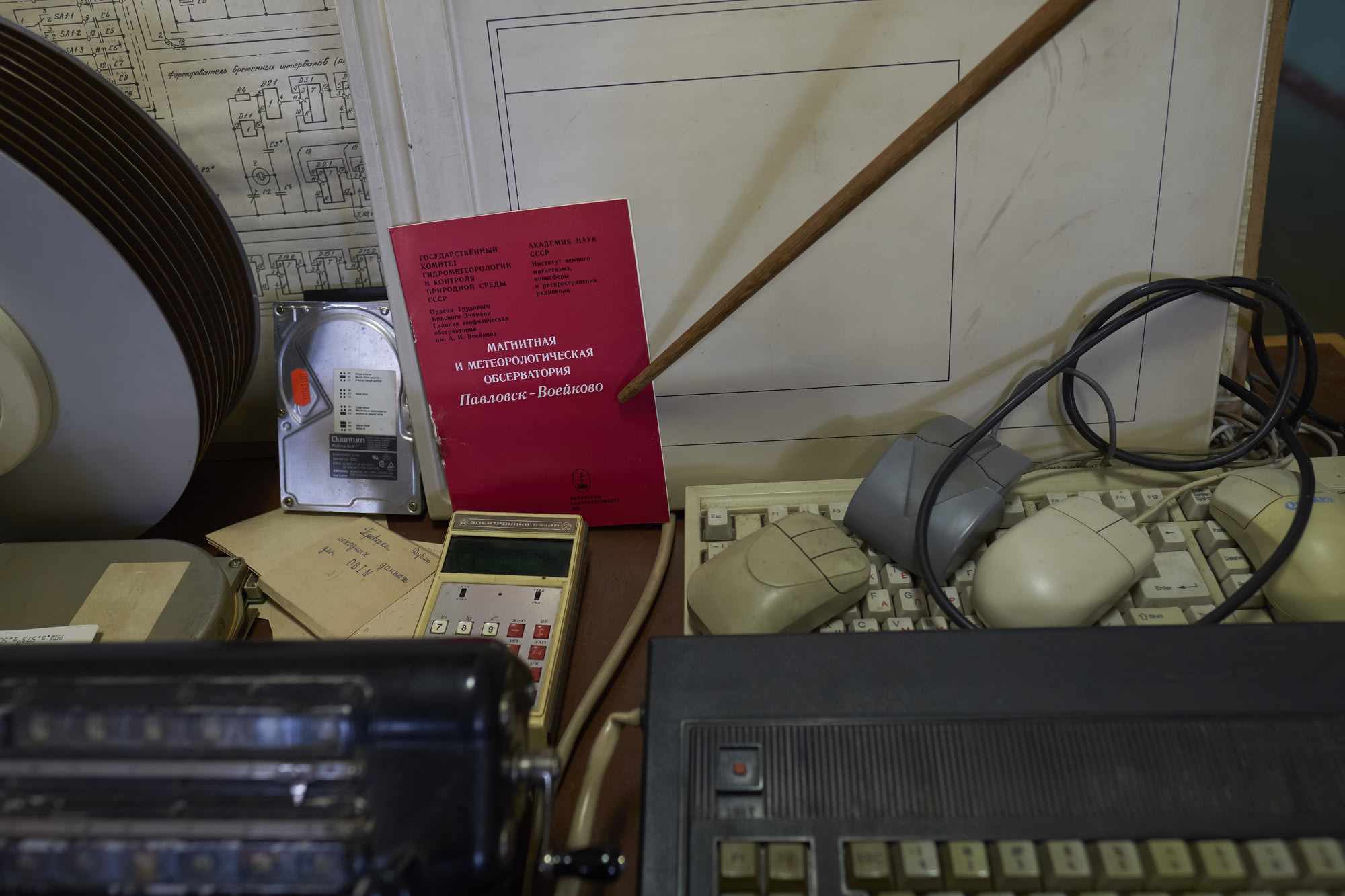

The photographs shown here were taken during a visit in August 2016, with some detail shots taken in August 2014.

On this day we go early, planning to come back at noon. We take the bus to Voejkovo and ask the driver to drop us off a bit before the village. The dog is barking in the guard house, but the gates are open, and we go through the green alley up the hill. As we approach the observatory, the antennae used for ionospheric measurements become visible through the bushes.

The main building proudly shows off its year of construction - 1961. Near the building discarded packaging lies, trying to blend in with straw and branches.

The sign reads: Институт земного магнетизма, ионосферы и распространения радиоволн имени Н. В. Пушкова РАН, «ИЗМИРАН», магнитно-ионосферная обсерватория, which is Russian for Pushkov Institute of Terrestrial Magnetism, Ionosphere and Radiowave Propagation IZMIRAN, magnetic ionospheric observatory.

The entrance welcomes us with an installation of a dysfunctional computer, a working soviet phone and a vase of field flowers.

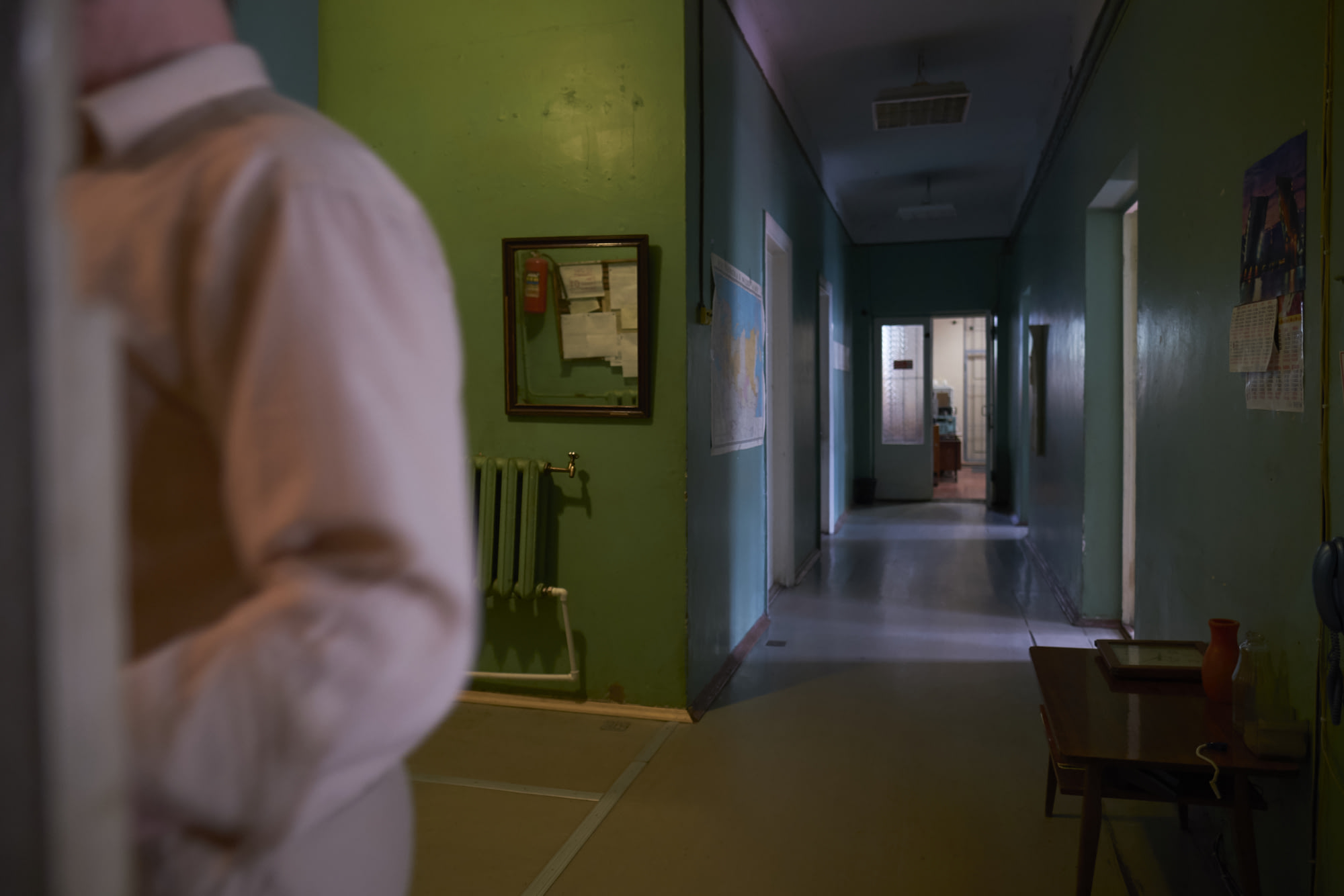

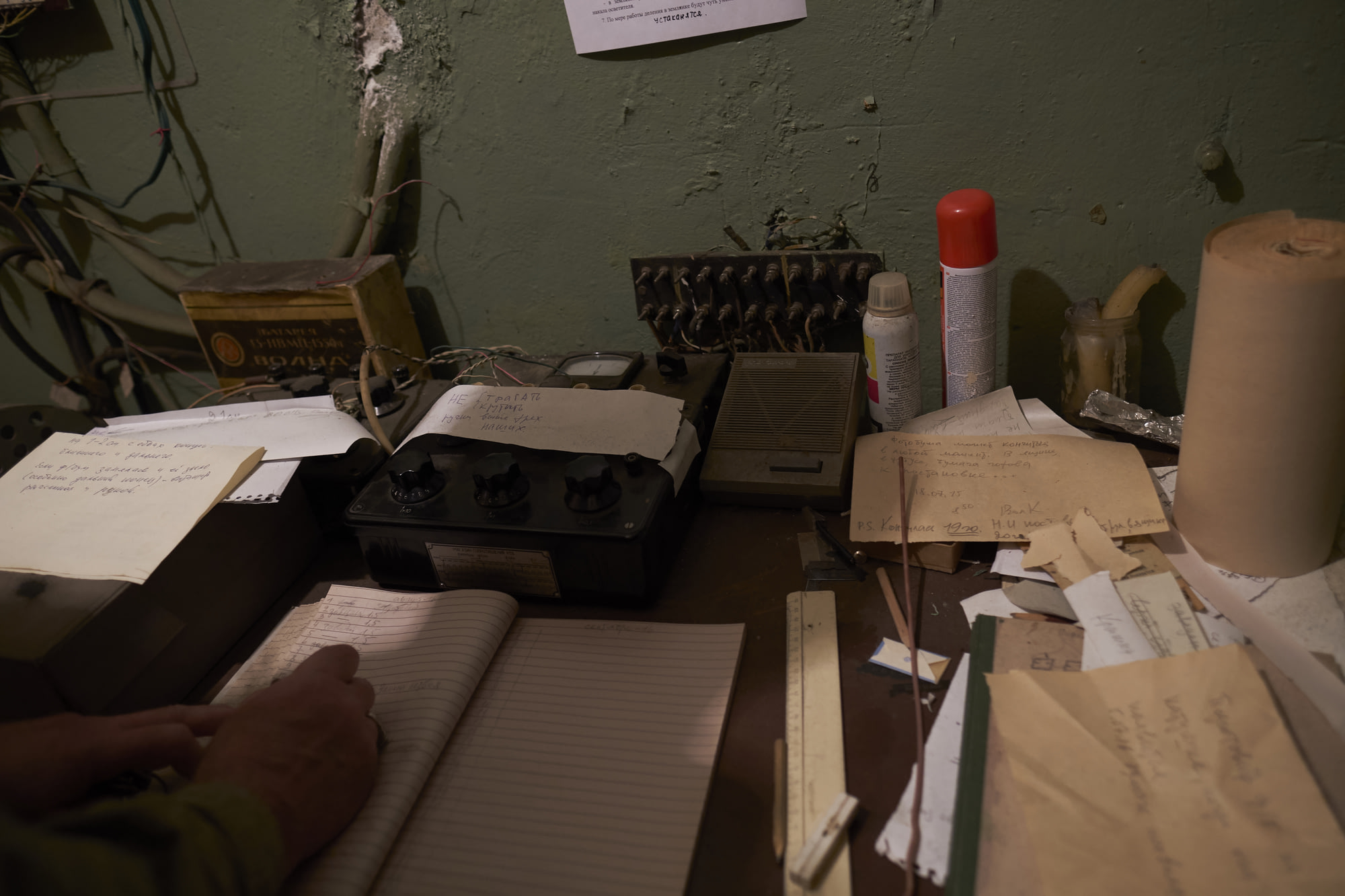

It smells of dust and old papers. Green and brown dominate the office spaces. Pictures of previous research teams hang on the wall; a sign next to the electrical outlets warns users not to plug in more than one space heater.

We are making tea and sandwiches to start the day. While the tea brews, there’s time to explore what the empty corridors hold.

These magnetometers built by Otto Toepfer & Sohn, Potsdam (a company disbanded in 1919) are not in use anymore. They stand by the window, looking too magnificent to be discarded. The model in front is Gr. Horizontal-Variometer №1 from 1900.

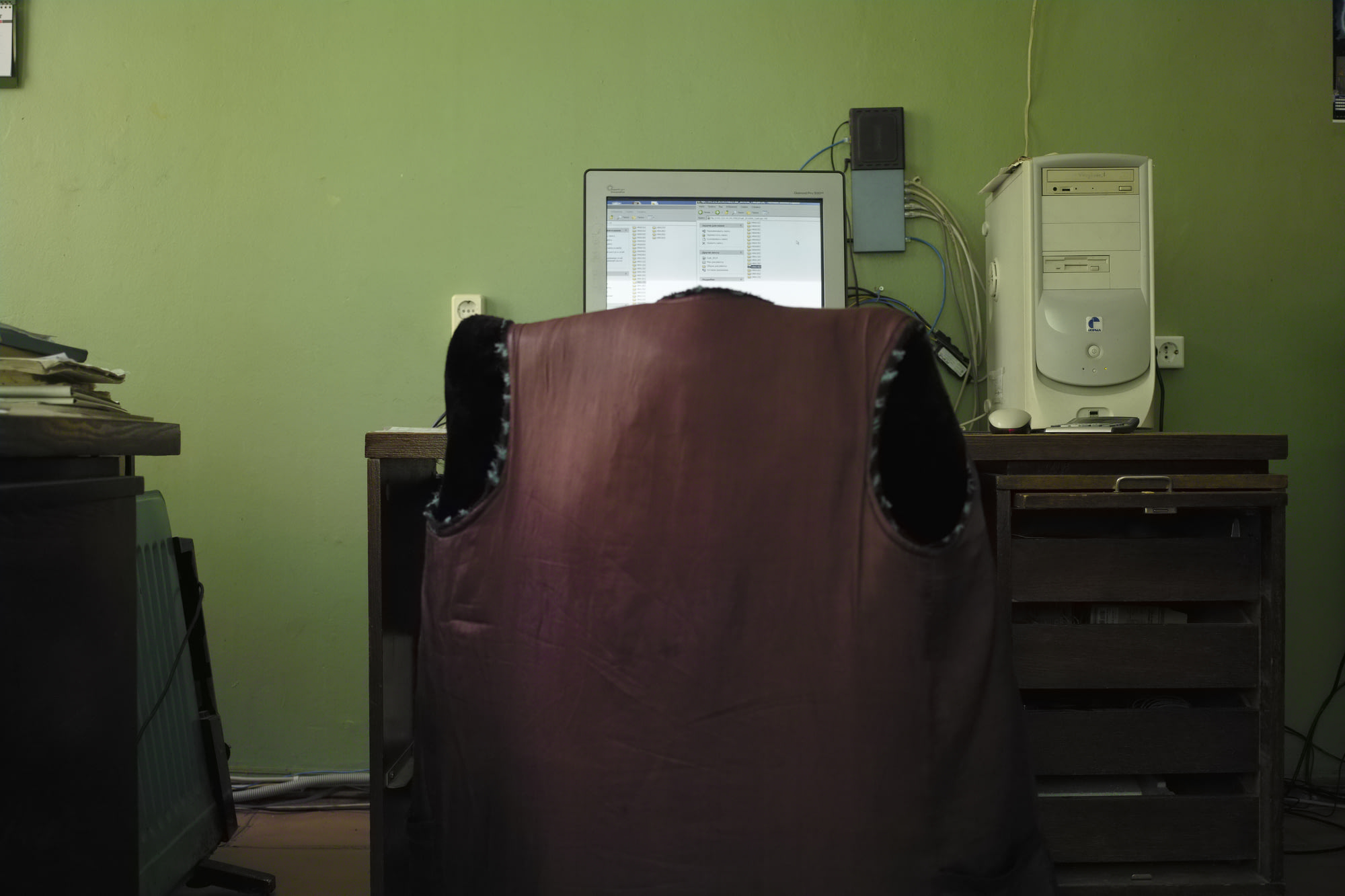

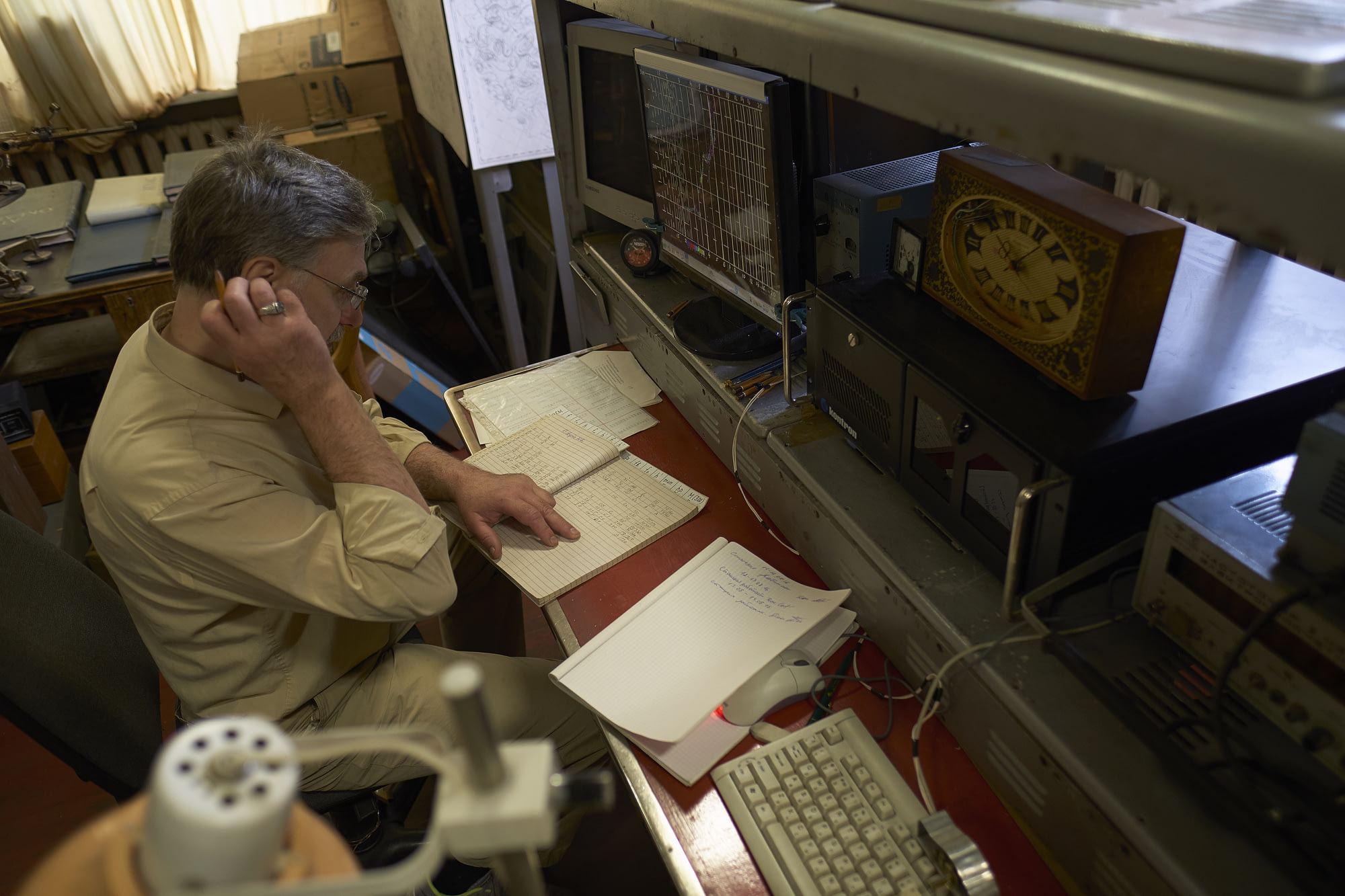

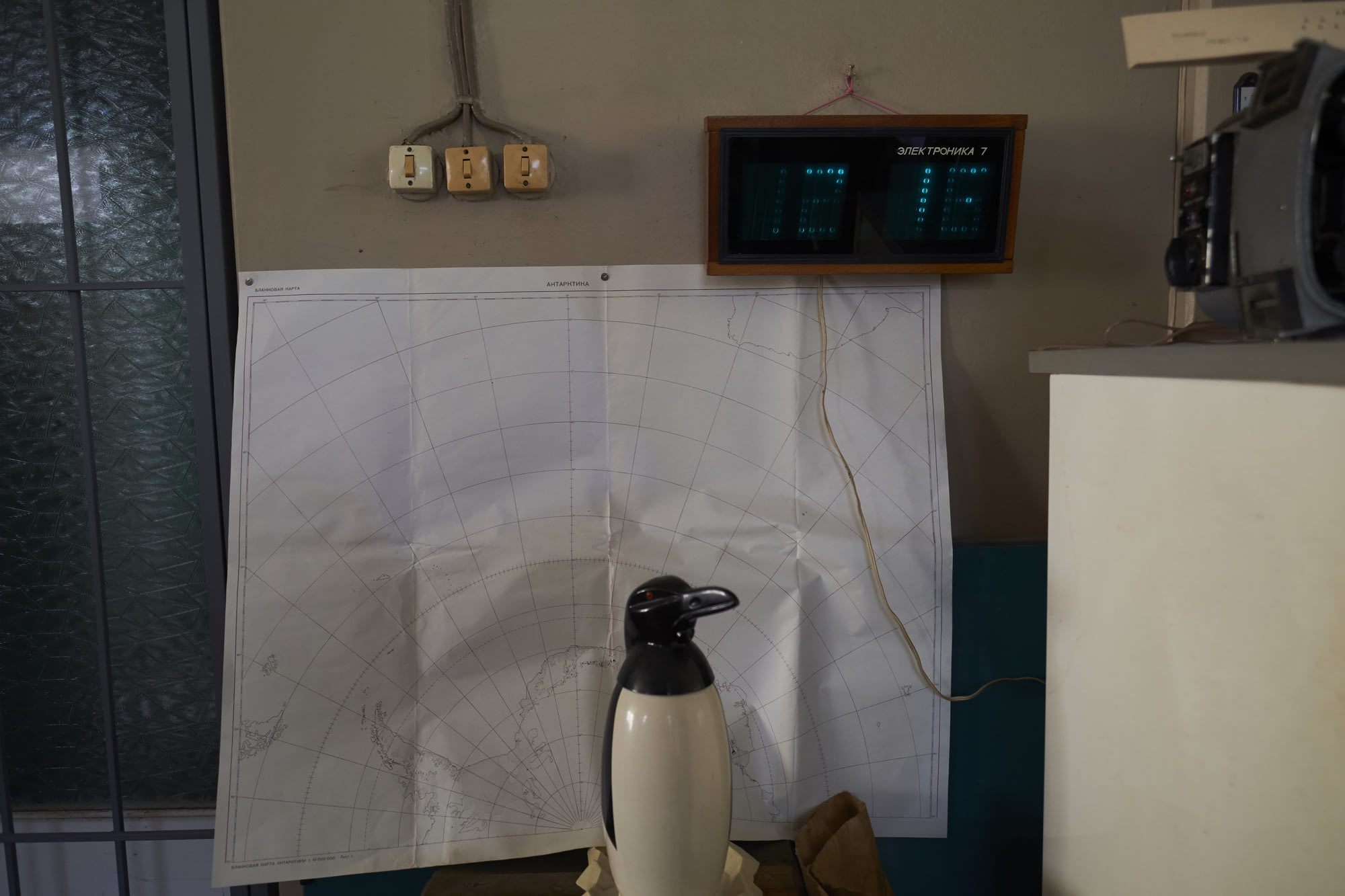

The main room is full of electrical equipment used for ionospheric measurement. A dozen years ago a server was acquired to make the work a bit easier, but the previous system is still in place as a backup. Fur coats cover the chairs, a testament to the icy temperatures of the place in the winter months.

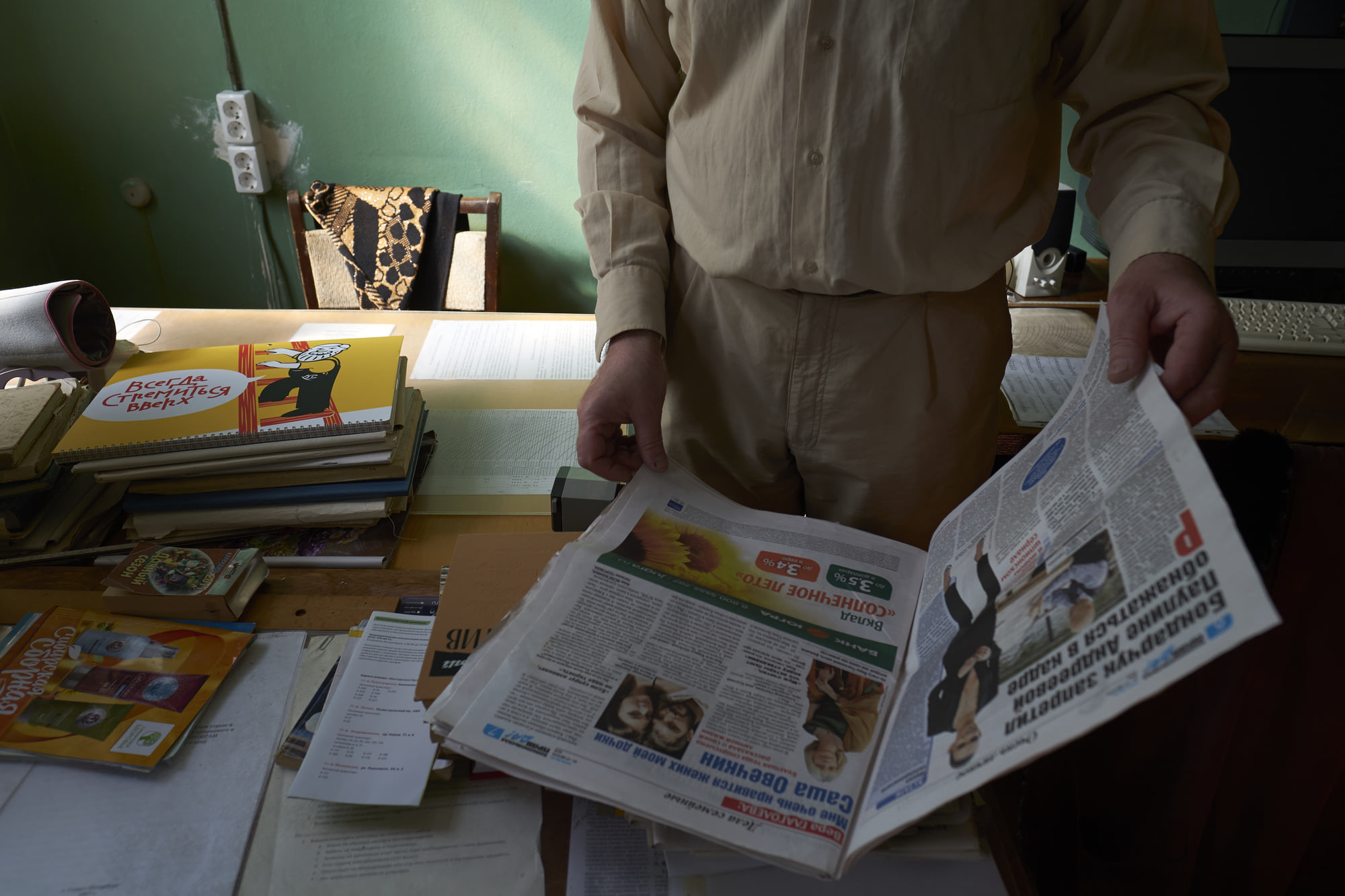

“Always aim higher”, says the calendar on the table. A Saint Nicholas icon hangs above the multichannel radio receiver, overseeing the room.

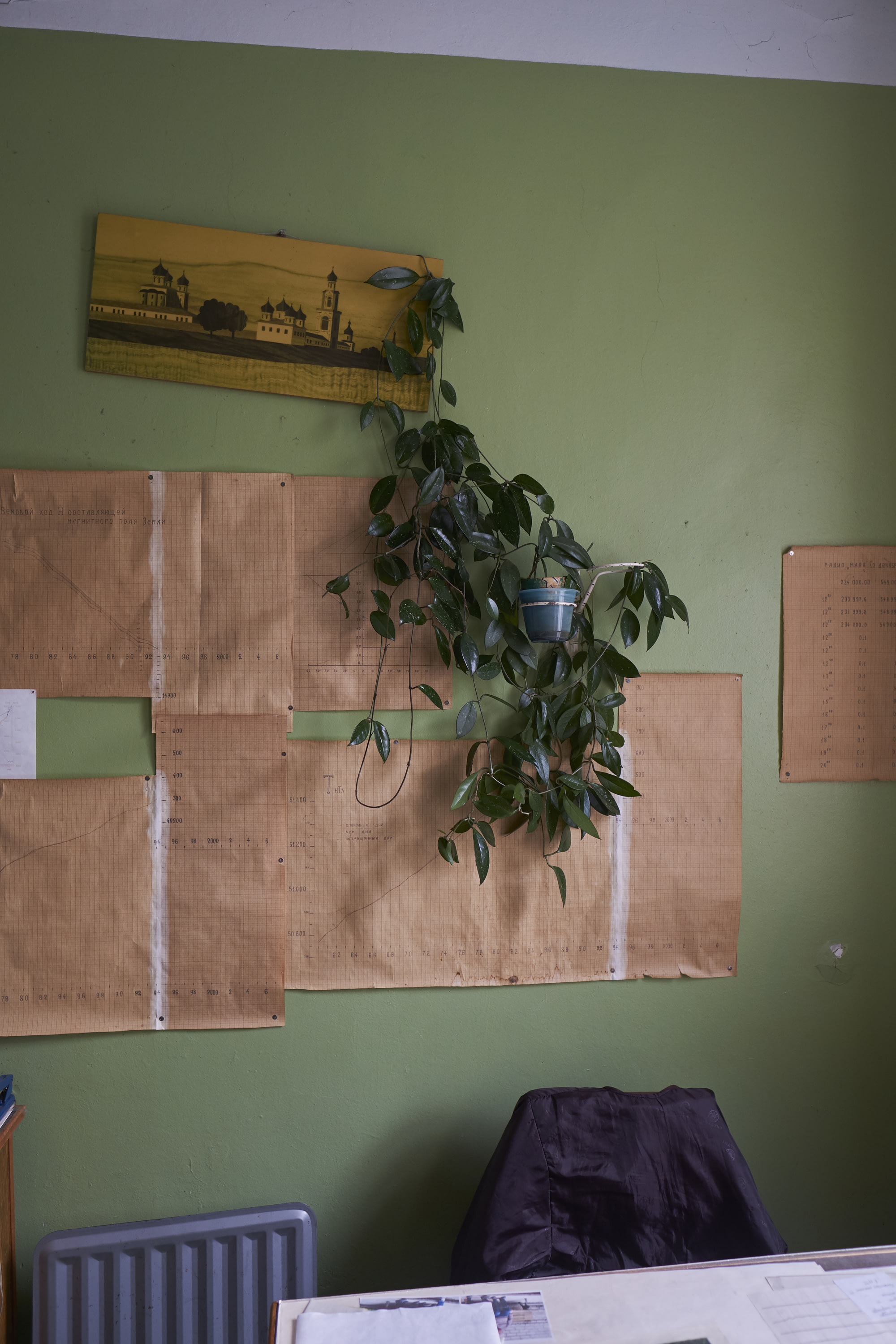

The chart of magnetic fluctuations over the course of the century is hanging on the wall. It stops at 1993.

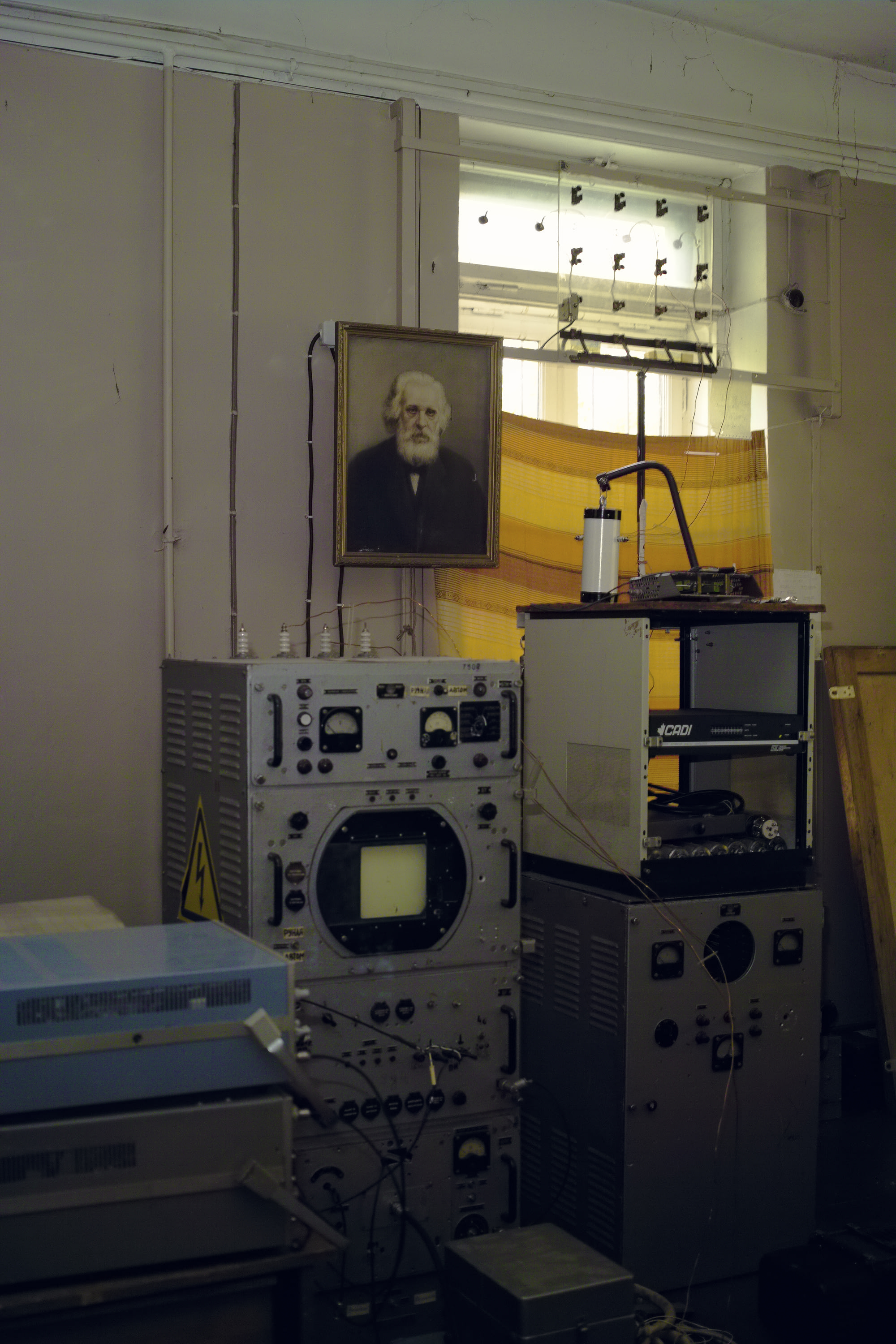

The portraits hanging on the walls do not depict specific academics, my father says - they signify the collective images of a theoretical and a practical researcher.

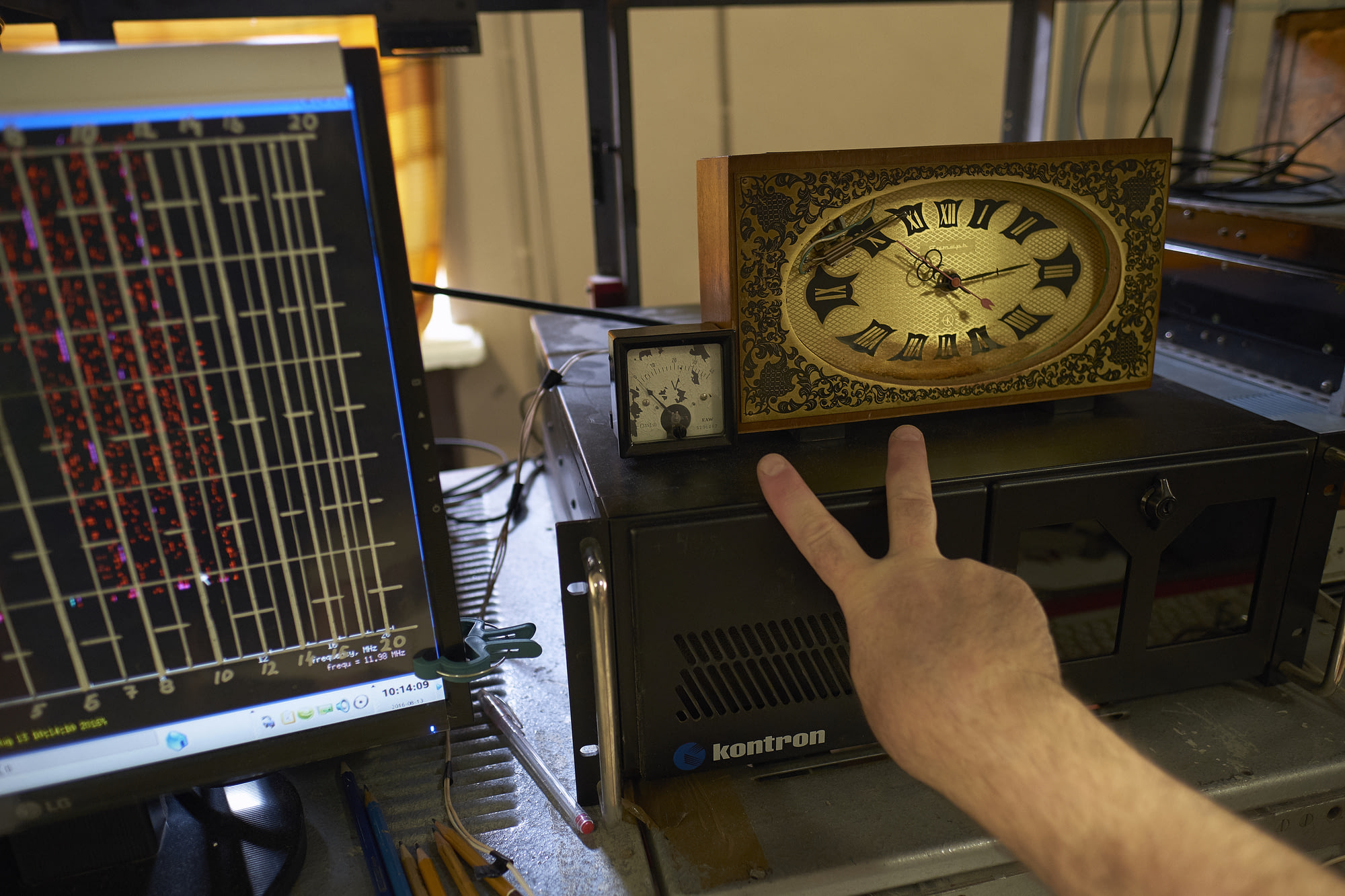

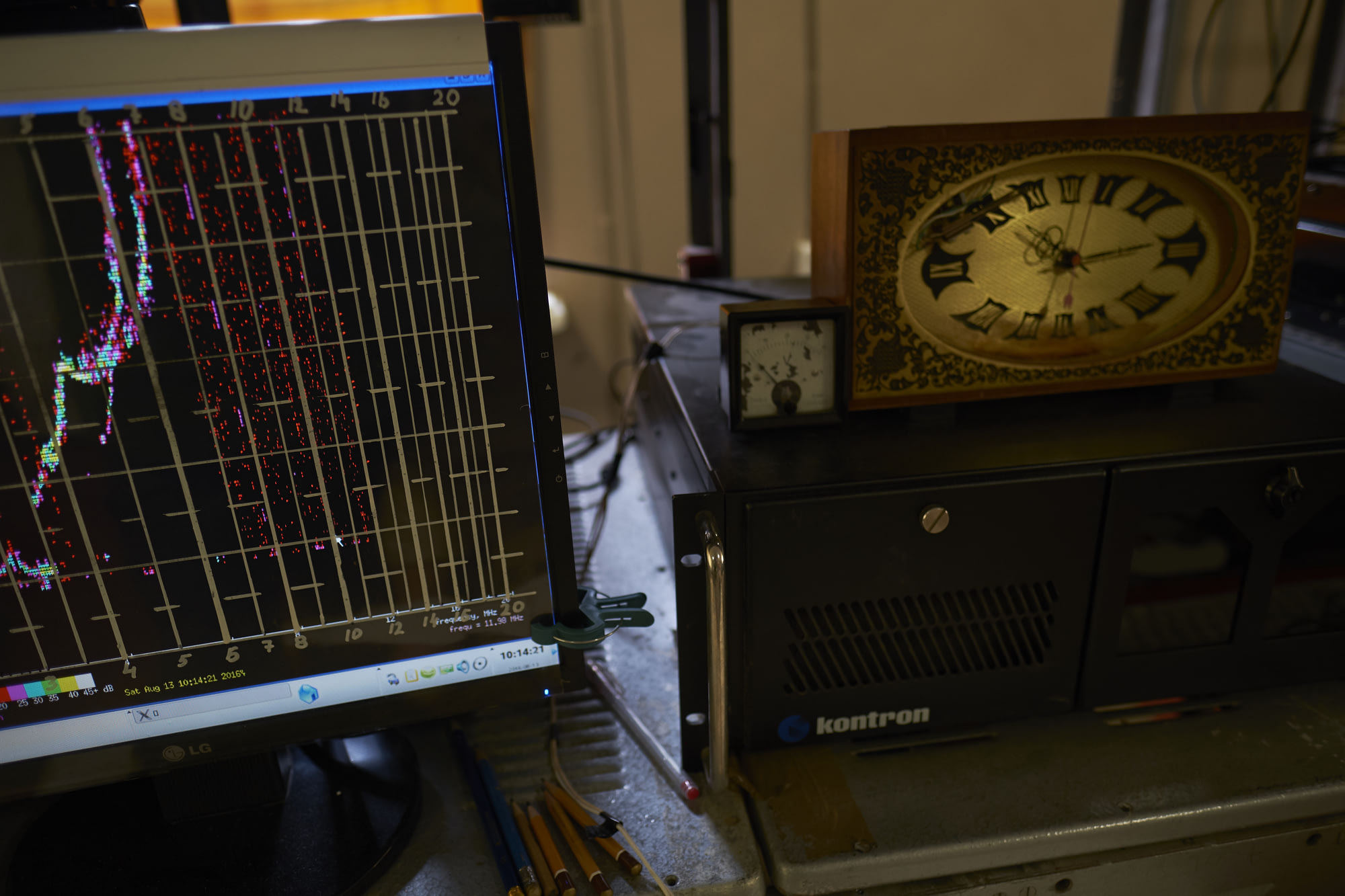

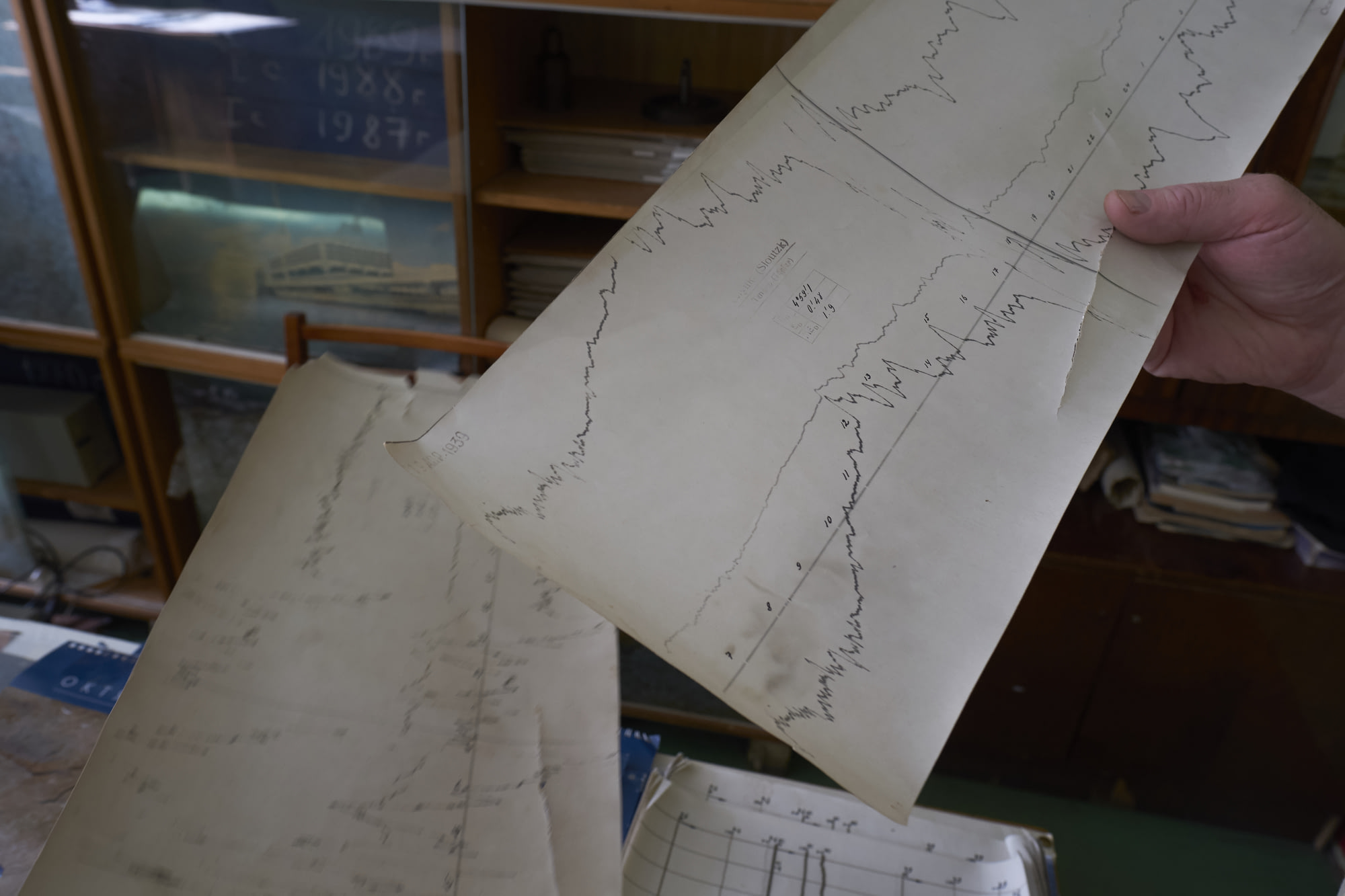

Ionospheric measurements are taken every hour. One antenna is used to send the signal, while the other listens for the reflection from the ionosphere. The delay between the outgoing and incoming signals is measured to calculate the height of the ionized layer. Different radio frequencies get reflected by differently ionized layers, which is why we get these graph representations of frequency responses.

The ionosphere is probed every hour. In soviet times the observatory had around the clock shifts to take measurements. A few year ago, my father automated the process: every time the minute hand on the soviet-baroque style table clock reaches 50 minutes, a wire is tripped, which activates a small motor to press a key on the keyboard. Sure, you could write a cron job for the Linux system running on the machine. But why interfere with a computer whose uptime is counted in years, if you can just build an electric hand?

It’s sunny and warm outside, so we go for a walk.

The next building houses a large dining room, mostly used for cooking and occasional parties.

Just under the archive of scientific documents, glassy witnesses of past festivities can be found. New-Years decorations hang in the corner, oblivious to the fact that the world outside is reaching the end of August. I like to think that the shiny garland has become best friends with the bland paint on the wall, both living on borrowed time, way past their expiration date.

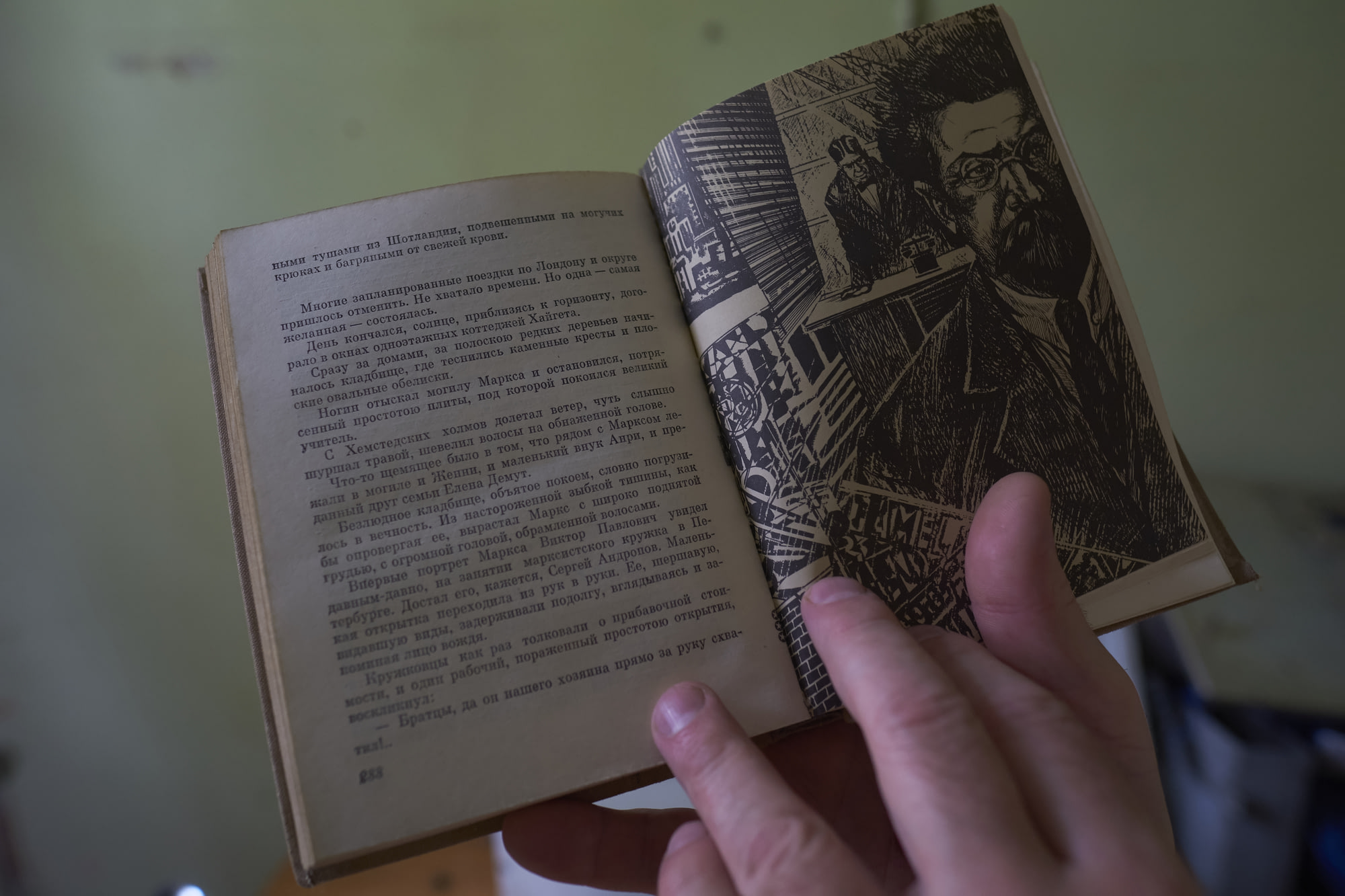

Next to discarded wires, monitors and electrical components, old books lie. In this one the protagonist, soviet revolutionary Viktor Nogin, is visiting the grave of Marx in London and “feels shaken by the simplicity of the tombstone, under which the great teacher rests”.

We leave once again to take the measurements of the magnetic field for the day. The first station takes electronic measurements of the magnetic field components. The door bears a chalk inscription, made by my father after attempted break-ins by people looking for scrap metal. In broken Russian it reads: HERE SCIENCE NO GO WOLF

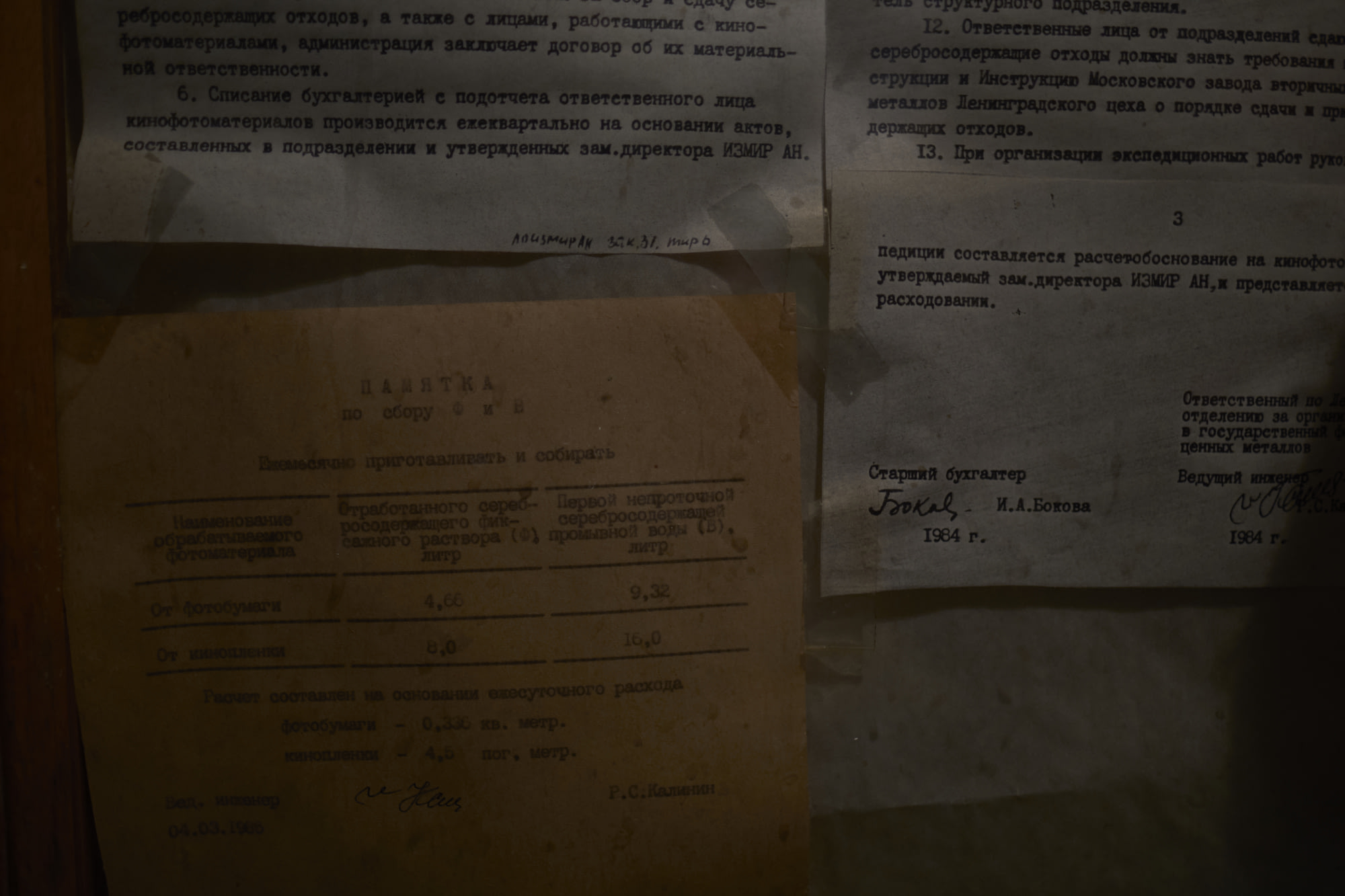

The second station takes the measurements on photographic paper. It was the earliest to be constructed and features thick walls with earth covering the sides in order to minimize electromagnetic interference.

Here too, a chalk inscription adorns the door: HERE IS NO EAT AND NO NON-FERROUS METALS HERE SCIENCE NO GO WOLF

Weathered by the elements it looks more and more like an ancient, indecipherable spell.

Photographic paper is secured on a drum, which slowly rotates - notice the manual winding mechanism. Light emitters are positioned a few meters away. Their horizontal alignments are influenced by tiny fluctuations in the magnetic field of the earth.

We take the recordings in a soft, velvety, light-proof bag back to the development room.

A note on the wall, dated 1986, dictates the amount of silver fixative that has to be recycled monthly. Magnetometric recordings dated April 1939 from a sister station in Slutzk lie on the table outside.

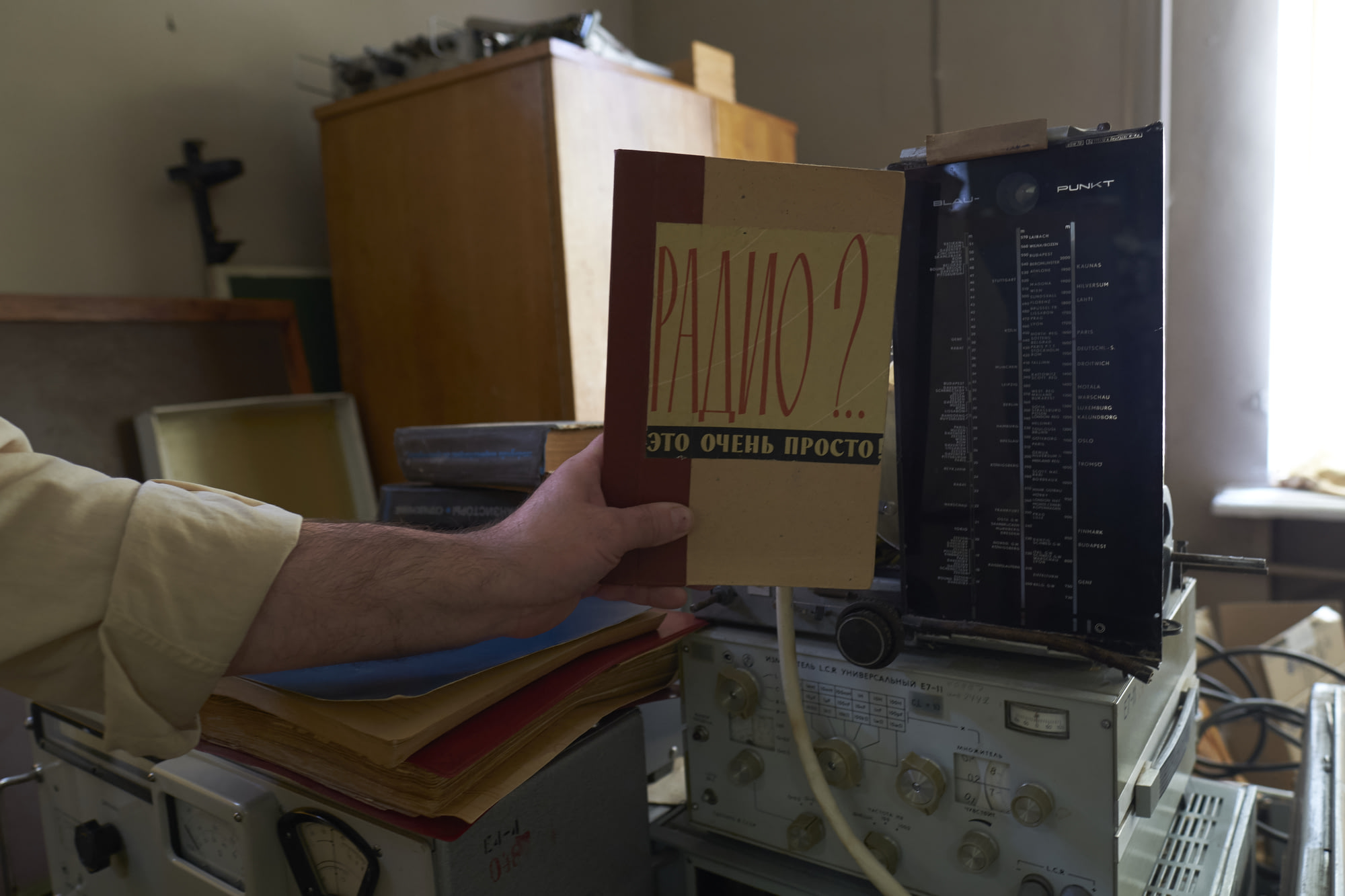

The light table in the ionospheric measurement room bears the map of where in the world magnetic measurements have taken place. “Radio? It’s very simple!” proclaims the reference book.

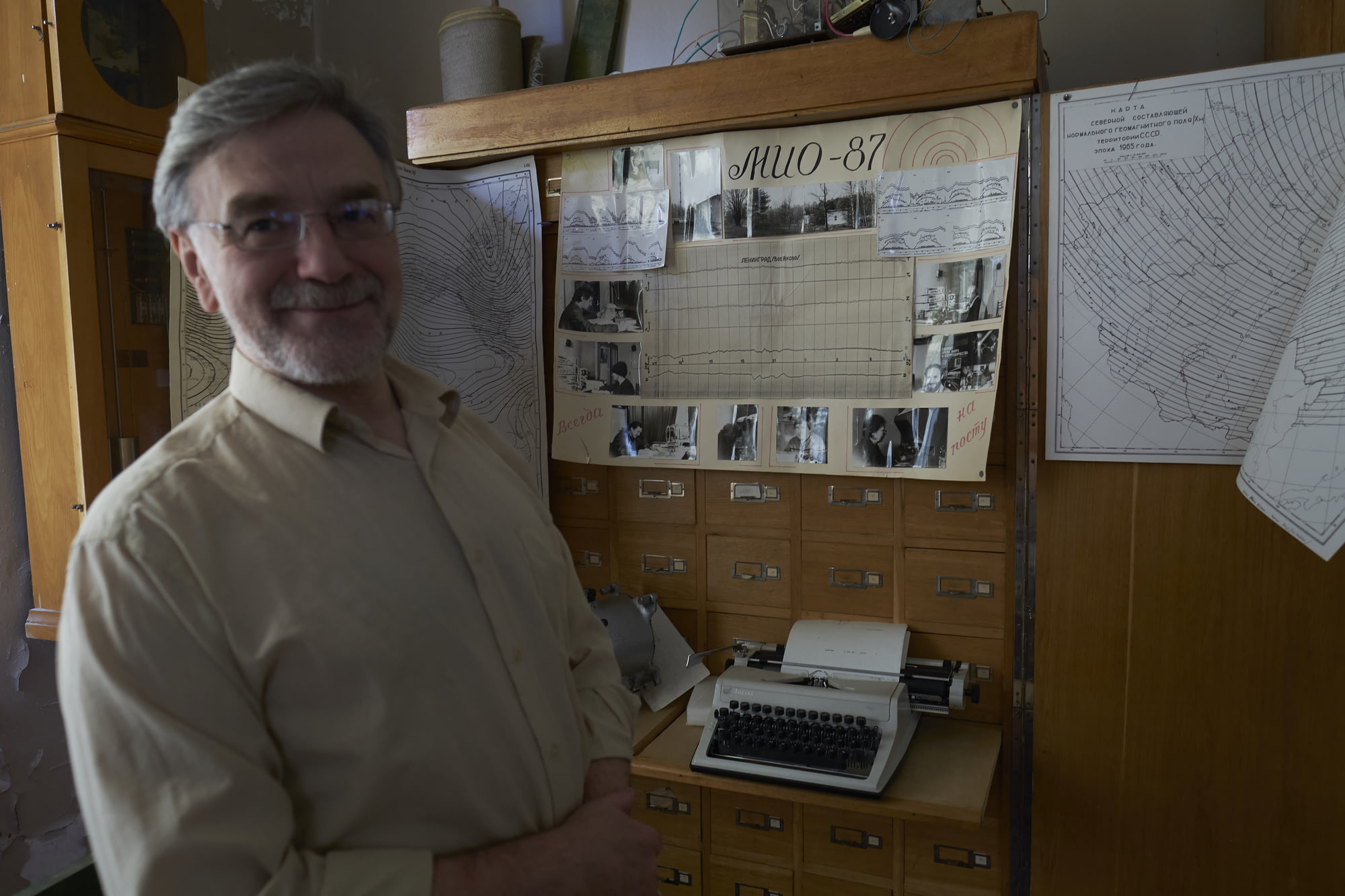

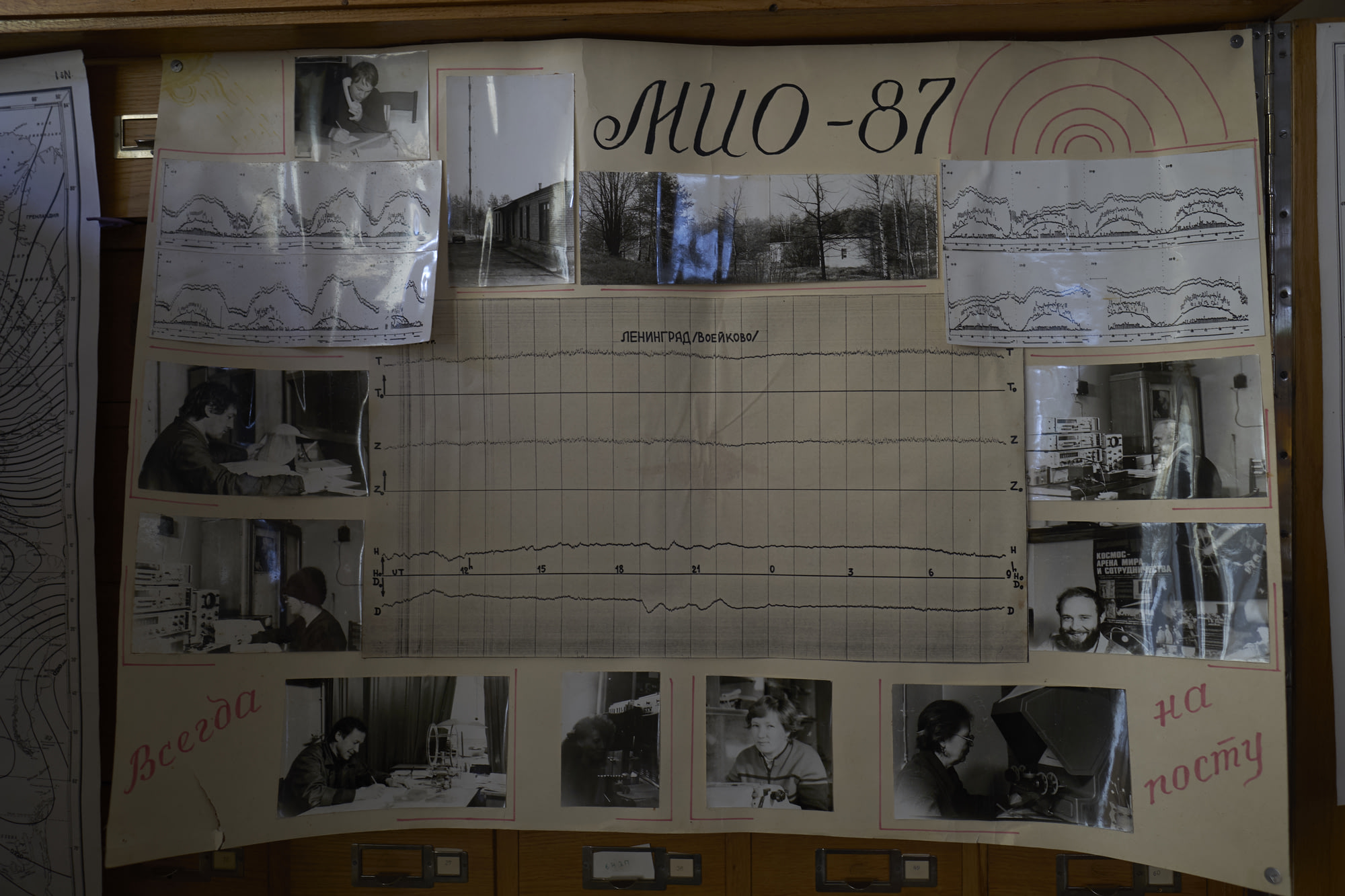

“Always on the job” was the motto of the wall newspaper that celebrated the observatory team of 1987. Some of the pictured team members have died, others are still working at the station. A monthly salary of 100-200 euro does not help to attract a new generation of workers.

The clock shows 12:16, it is time to leave for the day.

A bus stop away, in Voejkovo, a new wooden church has been built. Whether you find it beautiful or kitschy, it is one of the better examples of religious architecture in modern Russia. It is not my father’s church, but he wanted to pray to Saint Nicholas while we were there. A baptism ceremony of baby Michael took place as we entered, so we waited. The baby’s parents struggled to give answers to questions like why the Russian Orthodox Church is the true church, and what the name of its current leader is. They were asked to reconsider their life choices and come to the next sermon - if not for them, then for the child.

It seems oddly fitting that a man who spent his whole life trying to understand complex systems, an unwavering atheist in a dialectically materialistic world, would find peace and contentment in a system that is built not on understanding, but faith and devotion.

As my younger siblings grew up to a much more religious father, a question would eventually come up, one that I dreaded: Why do I not wear the cross? I would confess my godlessness, and their shock would only subside once I declared that I do agree with their beliefs, provided we use a synonym for god - love.

My father, the electrical engineer, does not speak about his beliefs with me.

There is not much to do at the magnetic ionospheric observatory these days, there are no breakthrough discoveries to be made. It is a strange place, lost in time, allowed to exist despite the lack of funding, the burglars looking to steal and sell copper wire, the coldness of unheated rooms in the winter and the lack of interest from younger scientists. It is manned by people who spent their youth at the observatory, who were brought up by the optimistic science fiction beliefs of the early sixties only to see it play out quite differently, but who still find pride in their work.

My father is currently writing his doctoral thesis in physics. At 61, he is the youngest one at the observatory. He stopped looking for all the answers in science. But he still got loads of questions.