Preliminary research results

When I first started this research, I thought about the feeling of arrival at home after a long journey. How for a moment everything in my home would feel alien, smaller or bigger, not quite how I remembered it. The space would feel like belonging to a stranger, and I would start to wonder what kind of life has been lived here before. Until, only a few seconds later, the objects surrounding me would take me in, would make me belong to them again. In this moment my mental image of a place re-aligns itself with the perception of the place. I arrive.

My plan then, was simple. I’d take this phenomenon, the short-lived feeling of re-aligning yourself to new surroundings, and find ways to recreate it in a performative way. Just by letting people perform familiar actions to out-of-place objects, or out-of-place actions to familiar objects, I’d make people see, with a fresh eye, their entanglement with the world around them.

This is a story of how that went.

Speculative topology

August to November 2018

I started my research with maps. Maps in their traditional, cartographic, sense, and also mental maps and the failures of mapping. I didn’t want to concentrate just on the imperfection of maps, since they are all flawed representations of a much more complex system. No, I wanted to bend their representative function to the breaking point but not further.

Before I introduce my experiments, I’d like to talk about a special map that I encountered when researching this topic.

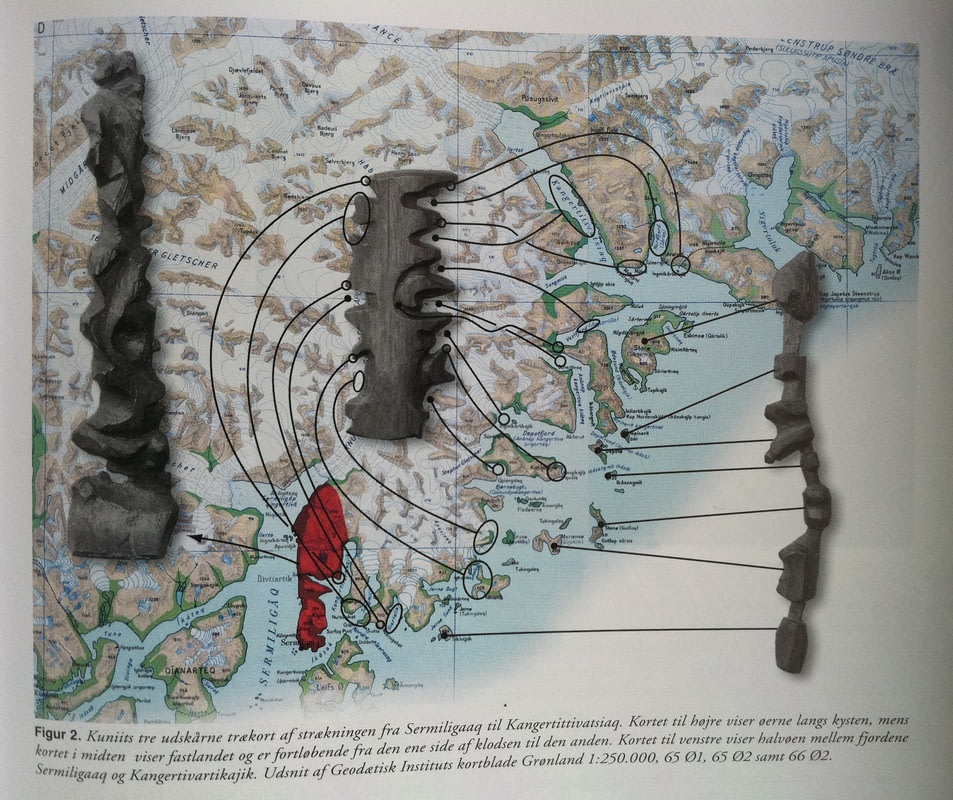

These are Ammassalik wooden maps: carved, tactile maps of Greenland coastlines.

They were designed to be read by hand, they float in water, they can be stored in a mitten and be read by night, snow or in any other condition. They serve as a great example of parallel map theory of hippocampal function (a neuroscience paper by Jacobs and Schenk), which implies that the spatial dimension is encoded in the hippocampus using two mapping systems - a relational, gradient map, and a topographic sketch map from positional cues. The mental maps we use in our human brains are created and stored by combining both systems.

The interesting thing about the Ammassalik wooden maps is, that it seems to be a purely relational, vector map, presenting distinct landscape features in relation to each other. This is in stark contrast to the traditional western map that we grew accustomed to, which takes the second, topographic approach.

My first experiment was to find some middle ground between the two mapping techniques: starting with the western, topographic approach, I would make it mutable, less stiff, move it towards a relational map.

I wrote a script that gradually removes empty spaces from a map using a seam carving algorithm.

This process compresses the maps, it saves all the important features and relations between objects, and it raises the information density. All for the small price of making the distance between depicted features a very speculative thing.

Arguably, distance is a speculative thing if we remember how wildly different the same distance will be perceived by a person climbing a mountain and a person driving a car in the tunnel through the same mountain.

When followed by an expanding step the algorithm produces some kind of a living, breathing map.

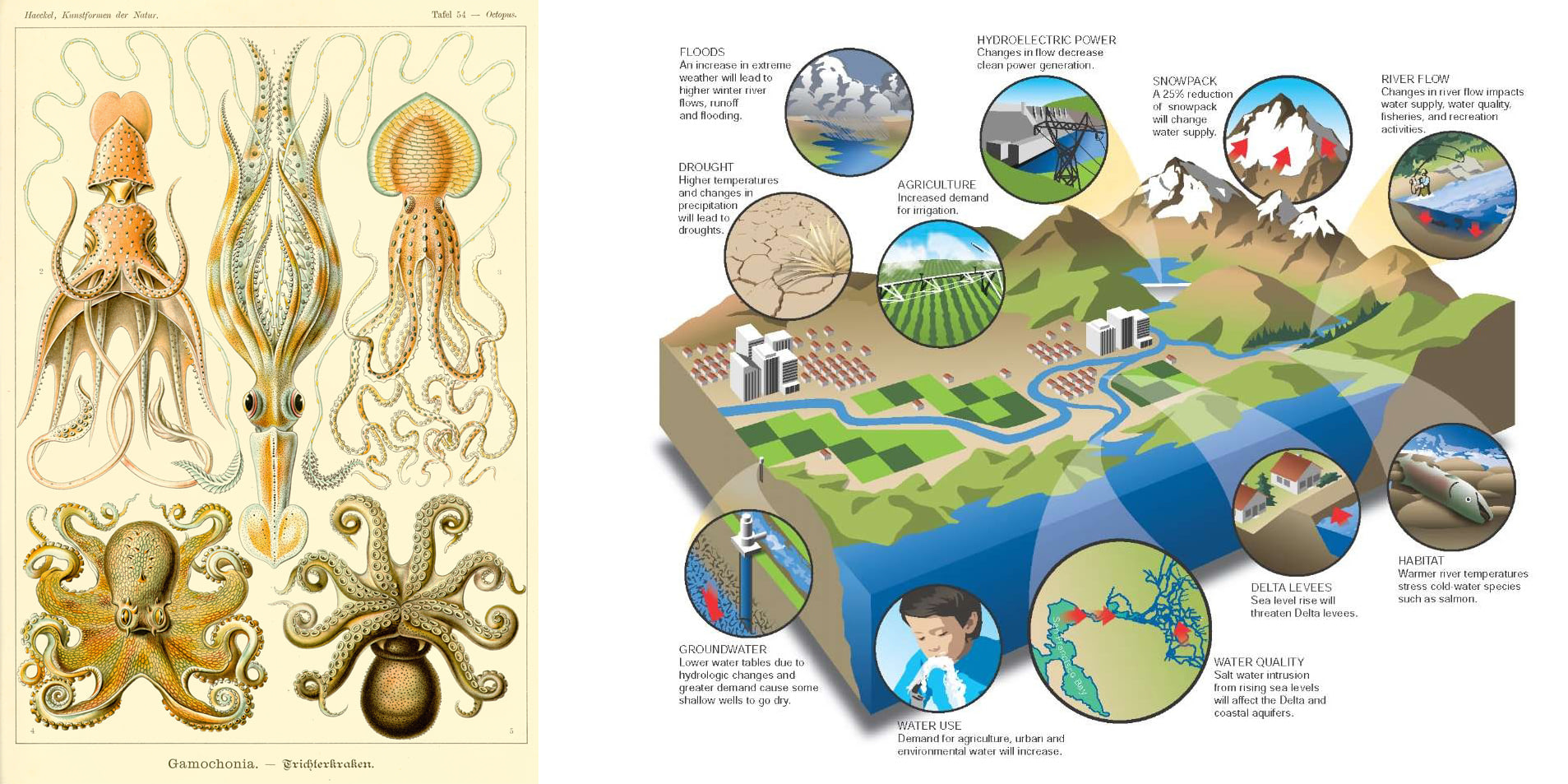

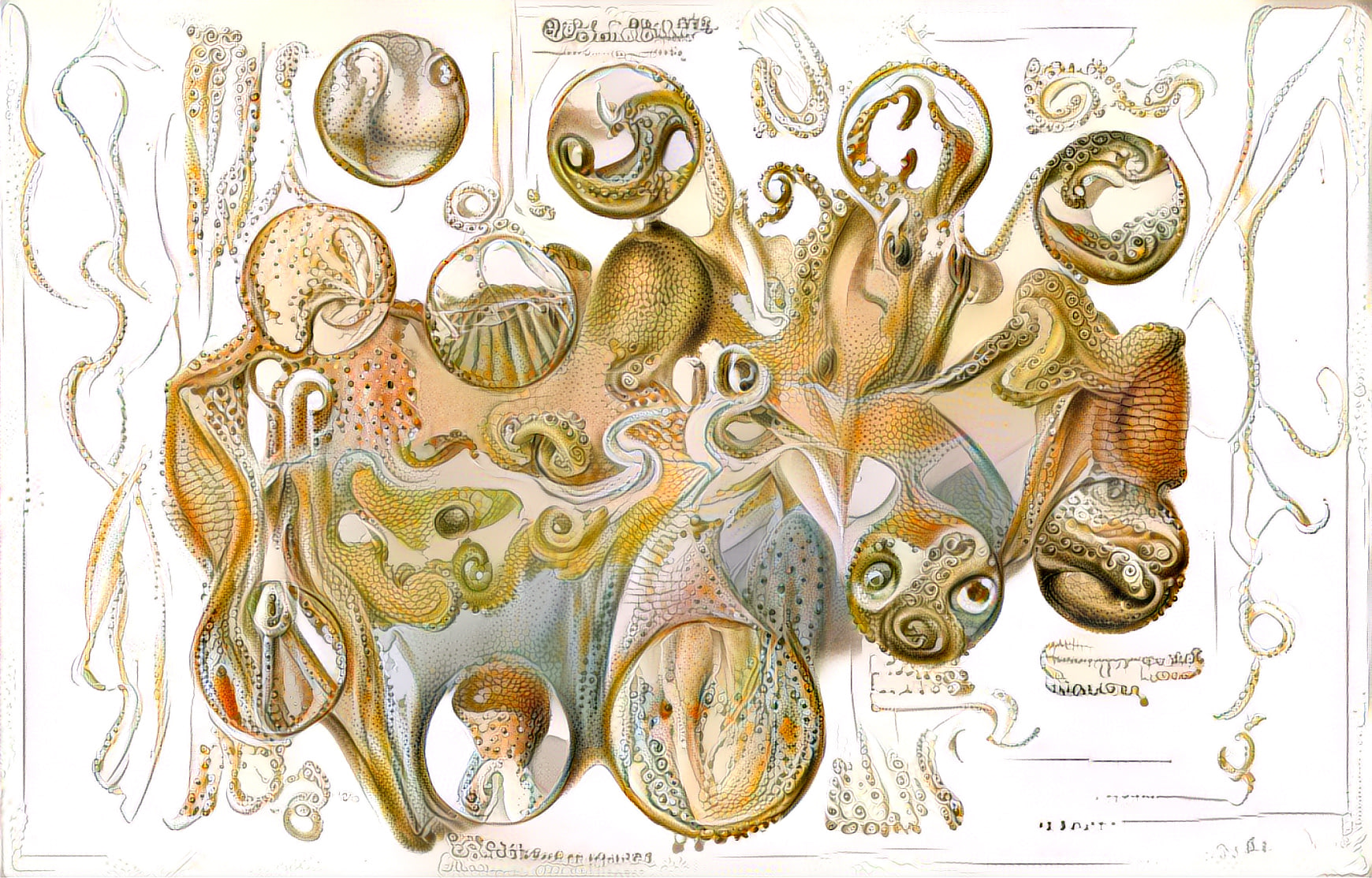

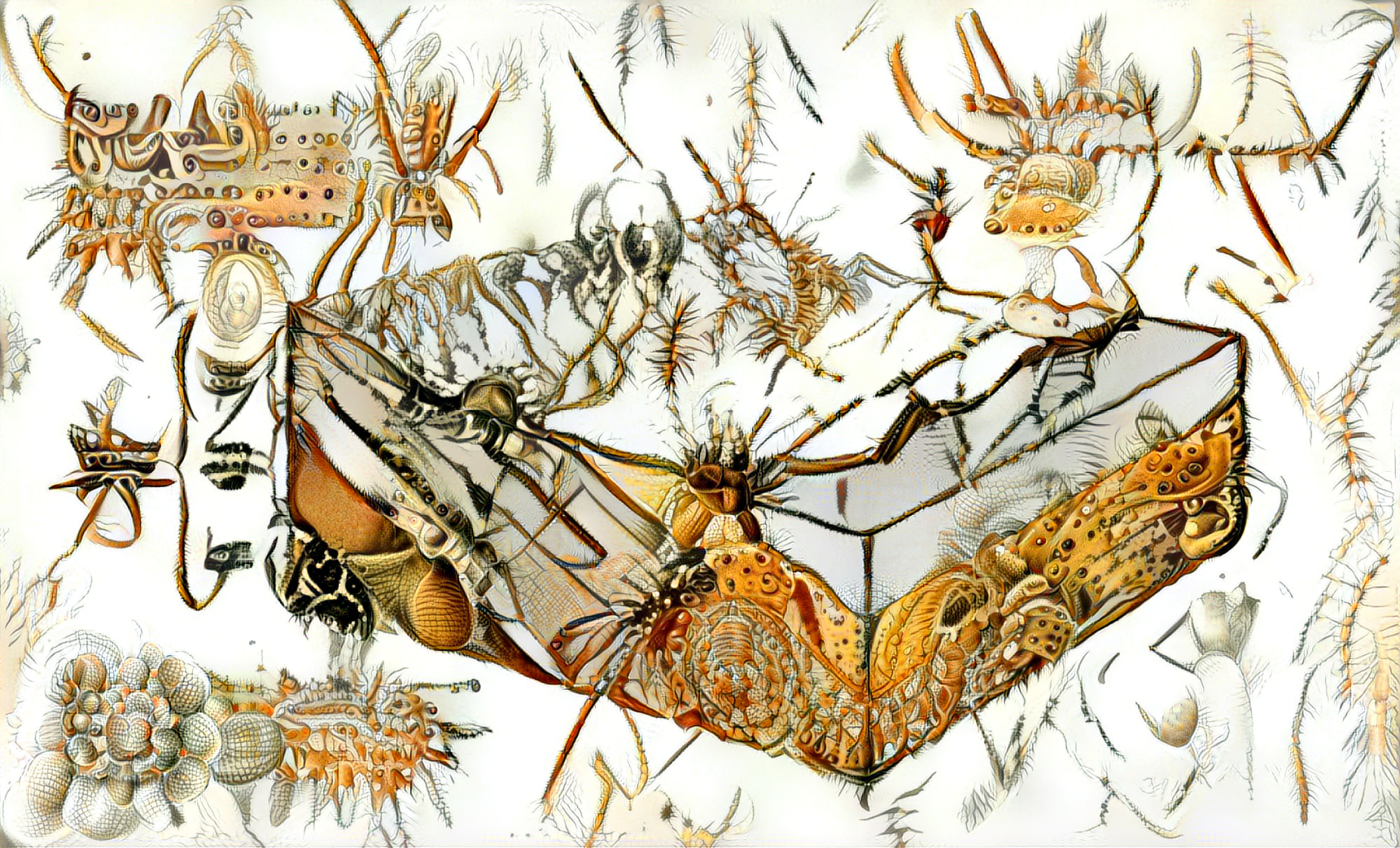

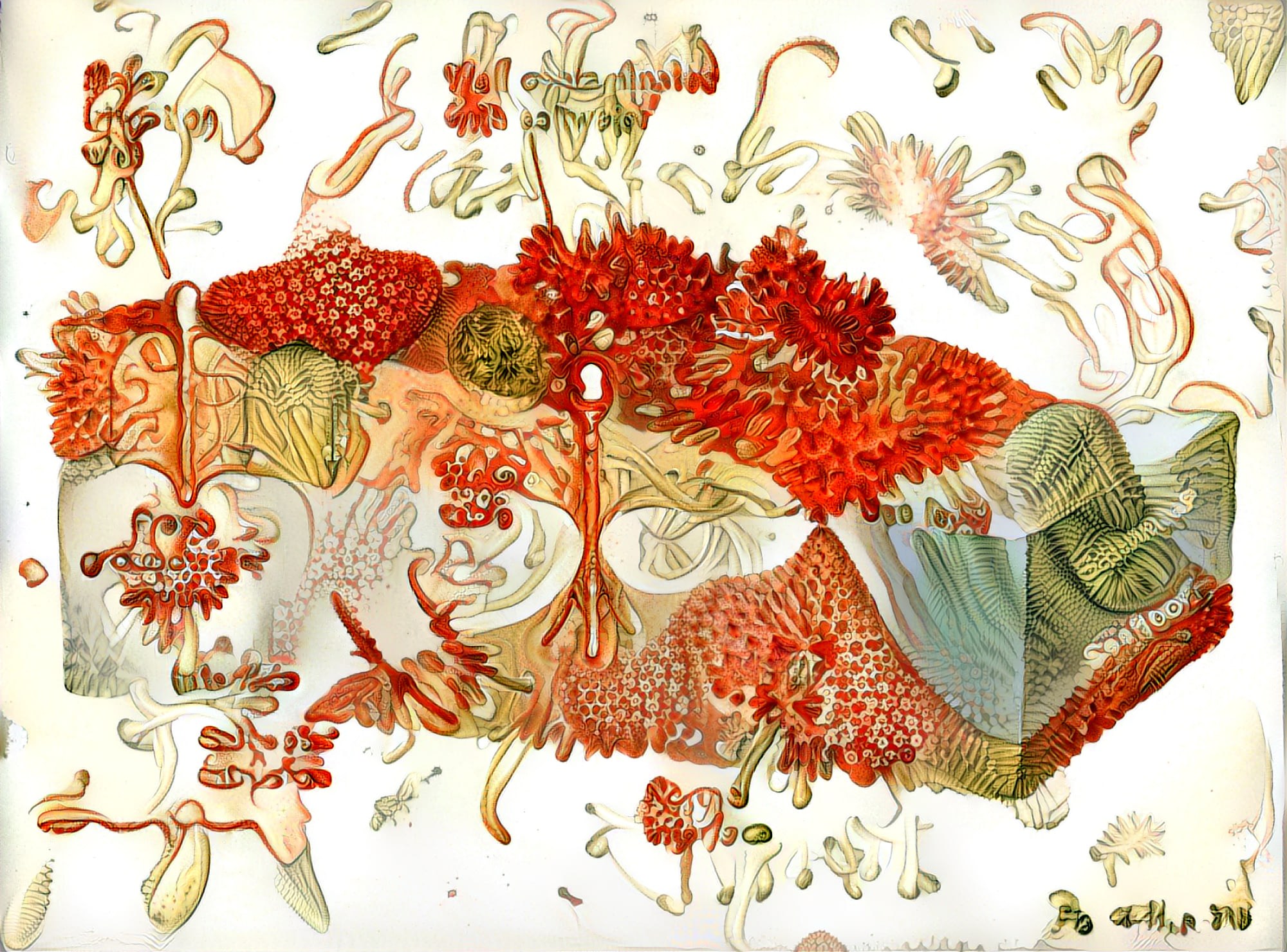

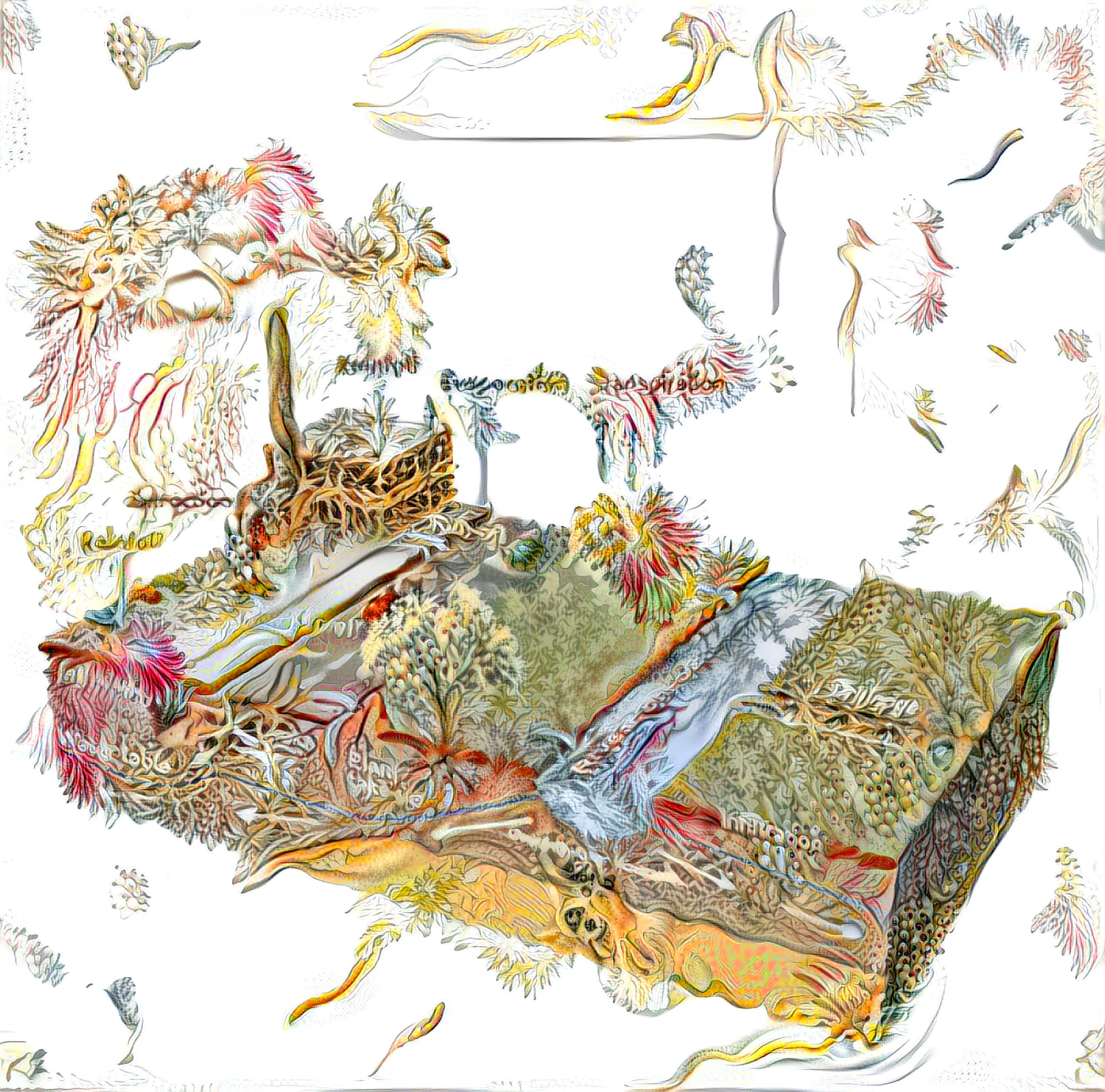

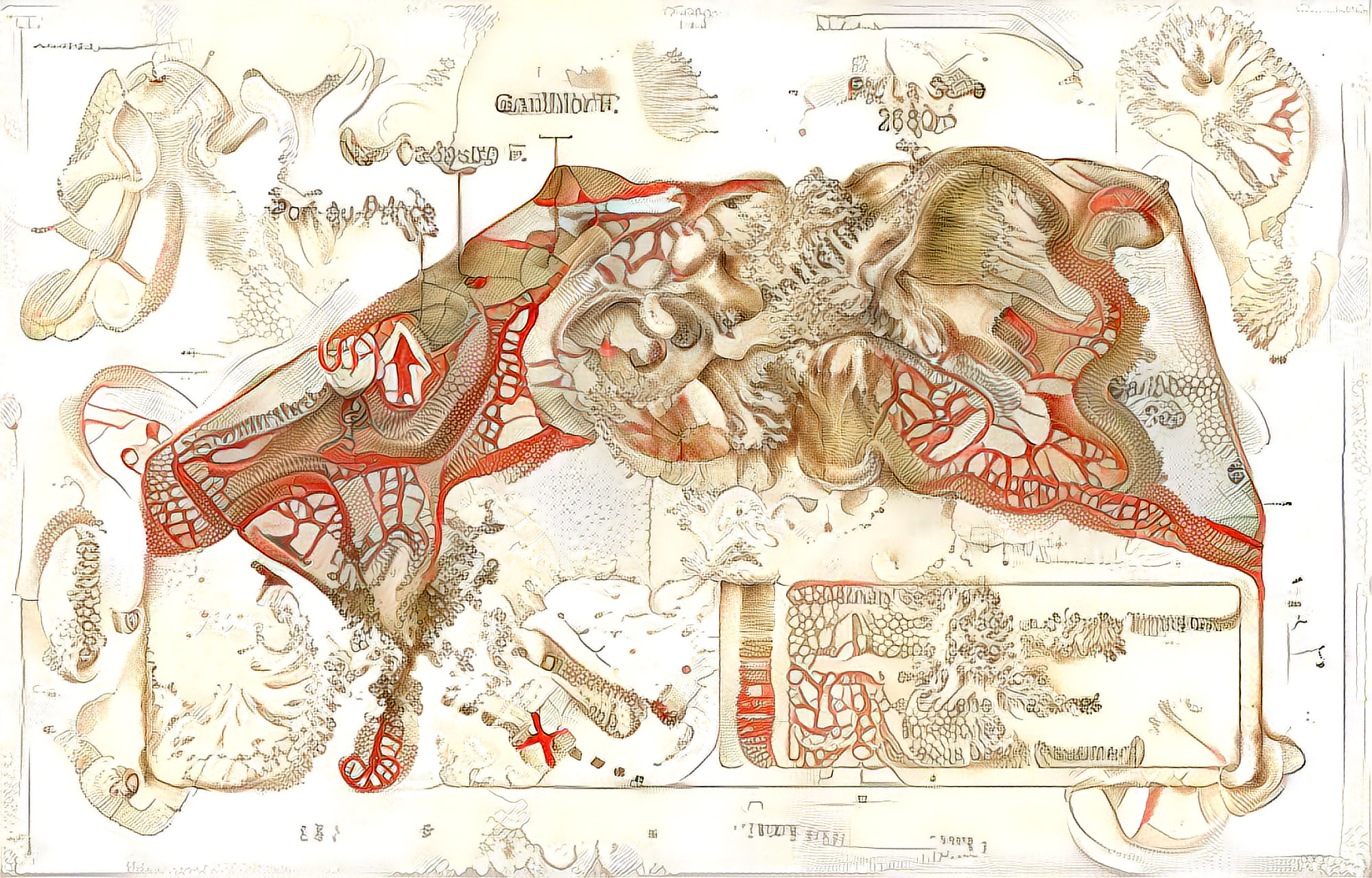

Encouraged by the success of the experiment I decided to try similar things with block diagrams, which are often used to illustrate complex system dynamics in earth sciences. Here, I used the neural style transfer algorithm to apply details and textures of animal illustrations to block diagrams of landscapes in which these animals might or might not live. The neural style transfer algorithm takes the block diagram as, in a way, a substrate, which is then populated by details and textures of the animal illustration.

I didn’t take just any illustrations - I used those created by Ernst Haeckel, the biologist who coined the term ecology, meaning the relation of the animal to its organic and inorganic environment. The resulting graphics produce an interesting take on ecology, blurring the border between an animal and its environment.

The prints were exhibited at Hack Morecambe in September 2018.

As the algorithm is non-deterministic, a few runs of it create seemingly moving, living landscapes.

Later I returned to the concept of organism as part of its surroundings by combining two AI techniques: body recognition and inpainting. The human body is recognized, then removed from the footage and quite literally replaced by a blend of the surroundings it was found in. The result is a ghost-like experience, «we are made of woods», you could think, «we are made of rock».

Of course, we are not literally made of rocks. But it does show in a novel way the belonging of the human body to the earth, to the ground that nurtures it.

Hitting the tree

October - November 2018

In this exercise, a tree is brought from the forest to the exhibition space. From its branches, a few batons are created by cutting away the unnecessary parts and fixing soft tape where the baton is to be gripped. When the group gathers around the tree for the performance, the batons are handed out without explanation, and the instructor begins pounding the tree with his baton, inviting others to follow suit. The beating of the tree continues until nobody wants to participate anymore.

I presented this performance at an exhibition, organized on the 8. of November 2018 at HfG Karlsruhe. I used a wild cherry tree which was felled on the 24 of October on request of a forest ranger, during routine forest maintenance.

The reactions to this act of senseless violence were quite diverse - some people were so eager to follow suit that their batons broke, others were repulsed by the act, some even pleaded to their friends not to participate in the violence, threatening a cancellation of friendship.

In the end, the tree got some new scratches on the bark. Dry leaves fell down on the floor. A few smaller branches broke, but otherwise the trunk remained intact. Most of the batons broke or were badly damaged.

Sure, it could be argued that every one of us is, indirectly, much more violent towards nature in our daily lives. The food we eat, the products and services we consume, all have a price that could be expressed in terms of violence, displacement and destruction. This price is hidden so well and abstracted away by dozens of intermediaries, so far disconnected from our lives, that a mostly symbolic but immediate, bodily experienced act of violence is perceived as a transgression.

Johanna Ziebritzki wrote down her impressions a few days after her participation in the excercise. I quote her response in its full length:

response to

Micha’s tree hitting, staged 2018/11/07, HfG Karlsruhe

by JZ2018/11/11

KarlsruheTo me, the situation was weird, it was odd, it was crooked. I observed people to be insecure about what was going on. I saw insecurity about how they should deal with the possibility (offering? invitation? request?) to hit the tree. They giggled, watched in awe and were disgusted or fascinated. Micha created a situation in which people had to decide how they would behave towards the tree hitting – they could hit, they could leave, they could collect all the sticks and boycott, they could question. Most people either hit or did demonstratively not hit.

Micha did not explain the idea behind it, which was to make something visible and enable to experience consciously common daily behavior. Destroy other beings. I knew about it, because we talked beforehand. When the stick was offered, I took it against inner resistance. I approached the tree and hit it, against inner resistance. I wanted to see if I could do it, and how it feels to hit a dead tree in an art school with people watching.

The leather shoes on my feet, the fish-spread I had just eaten, the wooden pen in my pocket had all come to me on a trail of suffering. If I would listen carefully enough, I would hear my shoes, the fish-spread and the pen crying silently, softly. But usually I don’t listen, otherwise I wouldn’t manage everyday life.

Hitting that dead tree was awkward, but at the same time, the stick in my hand and the sound of wood on wood felt familiar. I grew up in the middle of a deep forest in Germany. There, I often strolled around with a stick in my hand. The cloncing noise of wood against wood evoked past memories. Now I wanted to find out about my reactions. Thus I started actually hitting the tree hard. The bark broke open on the spot where my stick landed on the stem. Upon seeing this open wound, shame rushed from my brain into my face, I blushed. The shame signaled my arm to stop. No more hitting, no more hurting, no more deliberate pain. I had hit that tree deliberately, hurt it consciously. I had hurt me by doing it against my inner resistance, just out of curiosity, just because it was a staged situation. I felt like shit.

How is my ignorance about the cries of my leather shoes associated with the self-inflicted shame caused by my cruel behavior towards the tree? The amount of plants and animals we consume far exceeds what is necessary for our livelihoods. Now that my mind and heart listen to them with sharpened awareness, I hear their cries – and they are neither soft nor silent, but angry and loud. It is just that we have learned not to register anger, because we have no techniques of dealing with it creatively. We are scared of anger, because we perceive it as destructive. We are scared of destruction, because we perceive it as death. The trees are angry and hurt, just like us. However, they do not think they are the center of the planet and thus do not make such a fuss about their endangerment. They know that it is not they, nor we, who has the power of controlling life.

I put on my shoes, pick up my pen and write. We need techniques with which we become able to be angry, to be destructive and to perceive our being here as cycles of death, life and death in each moment. The tree hitting does not offer fun; it offers confrontation with oneself through in/action.

The wild cherry’s trunk was later turned into a chair by Oliver Boulam and Lukas Marstaller.

The hiding place

October - November 2018

This sculpture made of loam (and built by Lukas Marstaller and Oliver Boulam) looks a bit similar to a termite hill. It has two openings, just large enough to put your head inside. A grown person has to bow to put their head into the upper hole. For the lower one, they have to kneel.

Inside, it smells wet and earthy of loam and geosmin - a compound produced by the streptomyces bacteria that can be found in soil. Geosmin is in large part responsible for the smell of wet earth after a short summer rain.

In the other opening, it smells of sandalwood. The chemical compound called Sandalore is responsible for the smell and was shown by researchers of the University of Manchester to stimulate hair growth by regulating the lifecycle of hair follicles.

In both head rooms a sound can be heard. I fed hours of recordings of Sir David Attenborough and Werner Herzog to some neural networks called SampleRNN, which learned their voices and pronunciation. It did not, however, learn the content of their speech, and the sound generated by the machine is pure gibberish. While it may sound very similar to the two old wise men whom we learned to trust, telling stories about ourselves and the world we live in, it is devoid of all meaning.

Werner Herzog

Sir David Attenborough

As the visitors entered the caves with their heads, their sight was blocked by the darkness, the sense of smell filled by the smell of wet earth, their hearing calmed by the soothing, nonsensical narrations of the storytellers. With the most important senses hidden away in the head cave, only their derriere was exposed to the outside world. It might seem unfair to call the entirety of the human body - with the exception of the head - derriere. But for many of our daily activities, it is exactly what it is - a device to sit on.

The hiding place could be used as an apparatus for thoughtlessness, as it offers a lot and at the same time very little in terms of sensory stimulation. Visitors reported feeling vulnerable, exposed, but also calm and very aware of their body.

Soft entry

December 2018 to February 2019

There exists one thing that we are touching almost constantly, all the time. It is the ground beneath our feet. Walking, standing on the ground can often be seen as an act of rejection - we reject gravity, we push the ground away from us, we decline the proposition of giving in, of falling, of belonging to the ground. In such an antagonistic relationship to the ground it is not easy to see the act of walking as an act of touch. And yet, we touch the ground with every step, we feel texture, inclination, slipperiness and hardness of the materials we step on.

Soft entry was a proposed design for the entrance to the upcoming Critical Zones exhibition. A soft mat would cover the area, soft enough to force a re-adjustment of posture and changing the muscle tone of the arriving guests, but not too soft as to not divert the visitor’s attention to itself. This barely-perceived physical effect should change the feeling of the space in people entering the exhibition. It should change how they, bodily, relate to their surroundings.

I did a test with it for four days during the Critical Zones seminar in January 2019. It seemed to work well enough the first few times, though many tried to enter the room without stepping on the foam mat. This effect was compounded by the mat not looking like something that you would traditionally step on.

In general, it reliably created, in an unprepared visitor, the feeling that they enter a different space. A cover made of more common ground mats could further reduce the friction of stepping on the soft entrance area.

Pre-eaten food

December 2018 to February 2019

Traditionally, one would welcome their guests with food. After all, they just walked a long way to visit you and must be tired and hungry. I remember visiting friends as a child in Russia always meant, often before we even got to talk or play, sitting down at the dinner table with them and their parents or grandparents. Even if the family had very little food for themselves, they would share and not take no for an answer.

In January 2018 I combined the approach to food as a tool of welcoming with the wish to serve only the food that has been, in part, prepared by bacteria.

My friend Simon, me, and a multitude of Lactobacilli, Saccharomyces and other species created everything from scratch. Loaves of sourdough bread, two kinds of kimchi, swiss alp cheese made by Simon, ginger kefir and sauerkraut were served, complemented by lentil soup (for farting) and unpeeled peanuts (for the enjoyment of breaking the shell).

There was no feedback given, except on the excellence of the food, as everyone ate as much as they could and left soon after, surely to lie down at home and digest. It does feel like a purely bacterial cuisine could be an interesting approach to showcase the endless cycle of consuming food and becoming food for other species, but it also seems that taste would always get in the way of why and how the food was created.

Letting go

February - May 2019

This is a project that was shown both at the Otherwise Festival in Zürich and the Critical Zones seminar with Bruno Latour in Karlsruhe and produced wildly different results.

While nominally about letting go of things and attachments, it is in equal part about creativity. The group starts with a collection of materials laid out in front of them. These materials are non-objects, either discarded parts of human technology or parts of nature. The important thing is that they have lost their primary function, if they ever had one. They do not have straight surfaces or lettering or images on them. Just objects with complex shapes and textures: tree branches, bent spoons, eggshells, stones, pieces of thread, broken glass, wires, pieces of natural latex, bent metallic pipes, teared polyurethane foam and so on.

Out of this collection of materials, the participants are invited to build an object. Any object. Just by combining, bending, wiring the material together, or using a bright yellow duct tape.

After a few minutes, everyone has their object. It is never perfect, but instantly recognizable - all of a sudden it has a character of its own. The moment when most people don’t know what to add to their object anymore is the perfect moment to stop the process and ask everyone to give their object a name. Many are proud of their creation and they should be - they just built something out of nothing. Next, they will have to facilitate its destruction.

In one presentation I built a small platform overseeing a hall. In another, I just used a table. In both instances I gave everyone a simple task - to slowly push the newly created object of a cliff. A cliff high enough that, would we be the size of the object, a fall would certainly maim or kill us. And now, just minutes after being created, being given a name, it should die, be discarded back to the materials it was made of. I think that nobody really enjoyed that part of the exercise. But the instruction of pushing it off slowly surely helped experience the gravity of the moment and gave the creators just enough time to say their goodbyes.

The exercise was very well received in Zürich and not quite as well in Karlsruhe. My guess is that this difference comes from the Zürich group enjoying a much longer introduction, while in Karlsruhe the exercise directly followed just a bit of stretching as well as an exercise in giving objects around you new names, Keith Johnstone style. As in, pointing at the chair and exclaiming «kettle», pointing at a wall and saying «door» etc. Already at this point the participants were quite shy, probably not in small part hindered by the fact that there were two groups mixing together, very aware of their status within a group and quite cautious not to lose that status by doing something «wrong». That, of course, hinders all creativity, as it is the only way to do or say something uninspired. While feeling the uneasiness of the group, I still pressed on. Instead of allowing more time to arrive in the situation and trying to create a playful experience for everyone, I was very preoccupied with moving on to the next step, after all, I knew it could be a great experience! The fact that I tried to film the exercise at the same time certainly didn’t help.

There are good things about the exercise. It is giving everyone an excuse to be creative. The transition from creation to the impending destruction causes quite a rift in the mood of the group. The moment of the slow push that leads to a sudden fall can be cathartic. The structure of the exercise, however, could be more thought through, and a more light-hearted ending may be possible, something slightly less violent and more akin to slapstick comedy, like a trampoline placed right where the object is about to land.

Zwischenbäume

February - May 2019

A few years ago, I made top-down photographs of the space between trees. I was fascinated by the huge difference in attention garnered by something that has a name (a tree) and something that does not (the space between two trees). I took a camera and made huge, 200-megapixel photographs of that which has no name. I called it Zwischenbäume, a pun on the German word Zwischenräume - the gaps, the spaces between, and Bäume, the word for trees. I repeated the photographic process in Russia, Germany and Kenya, and had enough material for a show, but never showed it. I just didn’t know how to present it right.

That changed when I combined the photographs with the psychological technique of grounding. Grounding is used to cope with anxiety and PTSD, and often uses all five senses to move a person away from the feelings of danger and loss of control towards the actual reality of the situation, the physical reality they are currently in. Strategies may differ, but they all focus on what a person can, just in this moment, see, hear, smell, taste and touch. I added an imaginary layer to it - grounding while imagining being a tree.

When showed in a group setting, the process went like this:

I started with the usual warmup, some stretching, some shaking of the body, just to allow the participants to attend to their body instead of attending to the group, the social situation and their status within the situation. Depending on the group it may take some time and may need small exercises that are new to the participants, that take in their full attention. During my presentation in Karlsruhe I asked the group to do tiny movements that nobody could observe, nobody but them. It worked well, and everyone suddenly had a shroud of secrecy around them, trying to appear still and yet swindle the others by contracting some muscle in a tiny way or by moving some body part covered by clothing.

The next step was to attend to your neighbor’s body just as you attended to yours in the exercise before. I let the participants walk around the room until they felt comfortable moving through space, then asked them to let their shoulders touch the shoulders of their neighbor. This creates a non-visual connection to a body that hardly ever violates the personal space, as the shoulders are, socially, mostly acceptable to touch.

After the participants stood like this, in groups of two or three people, having found home or at least familiarity at each other’s shoulder, I asked them to look for a place within the room where they felt safe and at home. It didn’t take long, as humans are, like many social animals, experts in claiming space, claiming the area of power around them, and really do not like to give up the space they claimed. After letting everyone arrive at their chosen place for a minute, I asked the participants to show their place to their shoulder buddies, explain why they chose it, and how they feel about it. It’s not that the room had no features, but it had mostly the same features - columns, guardrails, walls - certainly not enough for twenty places to have some specific, outstanding quality, and still, people were very vocal about why they chose their place, going into detail about how they felt there, and letting the other person sit and experience it themselves.

Finally, the prints of Zwischenbäume were rolled out on the ground, and the pairs that were just talking to each other about their places got to stand in for the trees trunks, barely visible at the side of the photographs. I asked the participants to imagine being a tree, being exactly the tree from which position they were currently looking down on their surroundings, the tree which perspective they were currently taking in. From the perspective of that tree, to imagine their leaves flying in the wind, imagine their roots going deep into the earth, imagine the seasons change, imagine their neighbours and their future - standing there, in the same place, forever, until death.

Not sure whether the long preparation caused it, or the group had good imagination, but already after a few minutes many participants reported feeling strongly connected to the tree, to their imagined life as a tree, so much so that they felt strangely out of place when asked to leave their position to try and be the other tree.

This exercise had one of the most positive feedbacks throughout testing with different groups, it is unassuming enough so that nobody is afraid to ‘fail’ at it, and at the same time opens up a space for imagination of actually being another species.

The reading bike

May - July 2019

The reading bike is built upon a self-made cargo bike. Some wood scraps are added, some screws, a wheel from a broken bicycle, general leftovers from the process of living, objects that were once part of something bigger but lost their function and history. Out of these discarded materials, a contraption is built which rotates a tube in front of the driver when the bike is being driven. The tube’s rotation advances the roll paper and through that, the text. The reader must exert force, must change their position in space in order to change their position within the text.

I have presented the bike with two different texts. One was a poem by Hermann von Hermannsthal, a poet of romanticism. It is called Wenn ich den Wandrer frage (When I ask the wanderer), which could be translated like this:

When I ask the wanderer:

«Where do you come from?»

«From home, from home»,

he says with a heavy sigh.

When I ask the wanderer:

«Where do you go?»

«I go home, go home»

he says with a cheery tone.

When I ask the wanderer:

«Where lies your fortune?»

«At home, at home»,

he says with teary eye.

When he finally asks me:

«What distresses you so?»

«I cannot go home,

have no homeland anymore».

Which worked quite nicely as a reference to the imminent and seemingly inexorable loss of our planetary home to climate change - which was also the context of the exhibition. The reading bike makes you the wanderer, going on further through space in order to read the writing on the wall roll. The wobbly, insecure contraption on which you sit just adds the sense of precarity, the familiar sense that many feel nowadays when trying to imagine their future.

The other text that I used was a collection of haiku-like poems, written by me and intended to ground the reader within their bodily position on the bike, within the physical space they are in, as well as within the current moment in the vast history of earth. Here are a few:

above you

up in the sky

a swallow flies

two years ago

a couple kissed

standing right here

a tree stood once

where the column stands

on your right

when you inhale

the air you breath in

your neighbour exhaled

right through you

the Wi-Fi signal goes

checking your mail

when you were young

right in this place

two bees collided

a few lifetimes ago

a forest stood here

a forest will stand here soon

if you wait long enough

once in a while

a happy person walks by

The first version of the bike rotated the paper upwards, against the reading direction. That is why the poems are written in a way that allows them to be read from top to bottom and from the bottom to top.

The reading bike with the poems in German was presented at multiple occasions at the HfG Karlsruhe. The impact of the poems was seemingly overshadowed by the novelty of the bike. In no particular way do these poems invite a verbal reaction. They are not literary masterpieces. They are easy to grasp however and do tell a certain story. And somehow, as they are presented only one or two at a time, they do pique interest and invite the viewer to mount the bike to read more of them. Once on a bike, exposed, the experience becomes much more personal and intense.

In this way, the lack of immediate and full access to all the information fosters curiosity and enables an ever so slightly transformative experience.

Future research

Over the last year I had the opportunity to explore the topic of Arrival in depth. I had created dozens of experiments, artworks and gestures to test out different hypotheses about what it means, to arrive. I had the opportunity to present my findings at three conferences - OTHERWISE conference in Zürich, We are all able bodies at the CEU Universidad San Pablo in Madrid and Algorithmic Anxiety in Den Haag. I had five beautiful week-long occasions to present my research within the Critical Zones seminar with Bruno Latour at State University of Art and Design Karlsruhe.

I am nearly - but not quite - done with experimenting, I still want to explore a few more topics before I move to the production of a workshop series that would include the majority of the research presented here.

I want to explore the psychological and performative concept of authentic movement. Hardly ever do we really want to just lie down and do nothing, or move in a robotic way, or be subdued in our expressiveness. It mostly is a function of a coping mechanism or an effort to maintain social status. I want to look for ways of providing a safe and enjoyable way to move authentically, within the space of a museum.

Breaking is a very simple action, you just take an object and change its borders with your hands. I remember as I child I would break things all the time, but for an adult, breaking as an everyday action only expected and acceptable while cooking, and even there the opportunity to break is being slowly replaced by pre-made food. A new phenomenon, that of breaking open a postal box, unboxing the things bought online, is gaining in popularity. A search on youtube for ‘unboxing’ showcases hundreds of thousands of very popular videos that contain nothing but the recording of a parcel and then the packaging of a product being opened. I want to explore the empowerment and joy that breaking objects provides and find ways to use it as a way of arrival in space.

After researching these remaining two topics, I will focus on combining all previous research in one coherent workshop, with the aim of conducting the workshop during the Critical Zone exhibition at ZKM Karlsruhe, running from June to August 2020. The aim of this workshop/lab/playground will be to activate the visitors, to let them arrive differently within the exhibition, to open them up to new information through carefully designed interaction.

Timetable for future research:

August - November 2019

Research into authentic movement and breaking as affordance.

November 2019 - May 2020

Preparation and testing of a workshop/lab format that includes most of the presented research material on the topic of Arrival, especially as a new learning experience in the context of a museum.

May - August 2020

Deployment of the Strategy of Arrival as a tool of activating the visitors’ perception and imagination, over the course of Critical Zones exhibition at the ZKM Karlsruhe.

As sometimes the process is more interesting than the result, I also publish the unordered, uncensored notes I took during the time:

Strategies of Arrival: notes and process