In August of 2022, I went to St. Petersburg, Russia. I hadn’t seen my family for a long time, and with the start of the war, I felt it might be years before I saw them again. I flew to Helsinki and took an 8 hour bus ride to St. Petersburg - the city where I was born and spent the first thirteen years of my life. It was a very personal journey.

Having forgotten the charger for my camera, I mostly used my phone to try to capture the changing atmosphere in a very particular place.

Not knowing if I would be able to make the trip, I didn’t tell anyone I was coming. I just arrived one at my sister’s house in Koltushi, on the outskirts of St.Petersburg, and slowly worked my way towards the city.

The forest was warm, damp and peaceful.

Koltushi Heights, a hilly landscape formed during the last ice age, is located near Pavlovo – a town built in the 1930 for the scientists of the Ivan Pavlov Institute of Physiology.

Koltushi Heights has been declared a Unesco World Heritage Site. An oil pipeline runs through the site, bringing oil to a small port north of the city, where it is pumped onto tankers and exported.

Here it is, under the sand.

Bikers on motocross bikes and quads ride through the sandy, hilly landscape.

Right into the World Heritage Site, a cemetery grows.

A church has recently been built near the entrance to the cemetery. Across the road, the red flowers of Ivan Chai (Fireweed) have ripened and are getting ready to fly.

It is said that Ivan Chai grows best on the ashes of burnt houses.

If true, it will soon cover the site where the house of physiologist (and Russia’s first Nobel laureate) Ivan Pavlov once stood.

There are rumors that it was deliberately burned down to prevent it from being turned into a museum.

In the early 1930s, a number of cottages were built around the Institute of Physiology to house the families of the scientists. My father, after working at the Institute for some time, still lives in one of the cottages.

My father uses only locally sourced materials in his greenhouses. The discarded wooden window frames are turned into walls, roofs, and even seaworthy boats.

Last year he built a rowing machine out of the remnants of a bike.

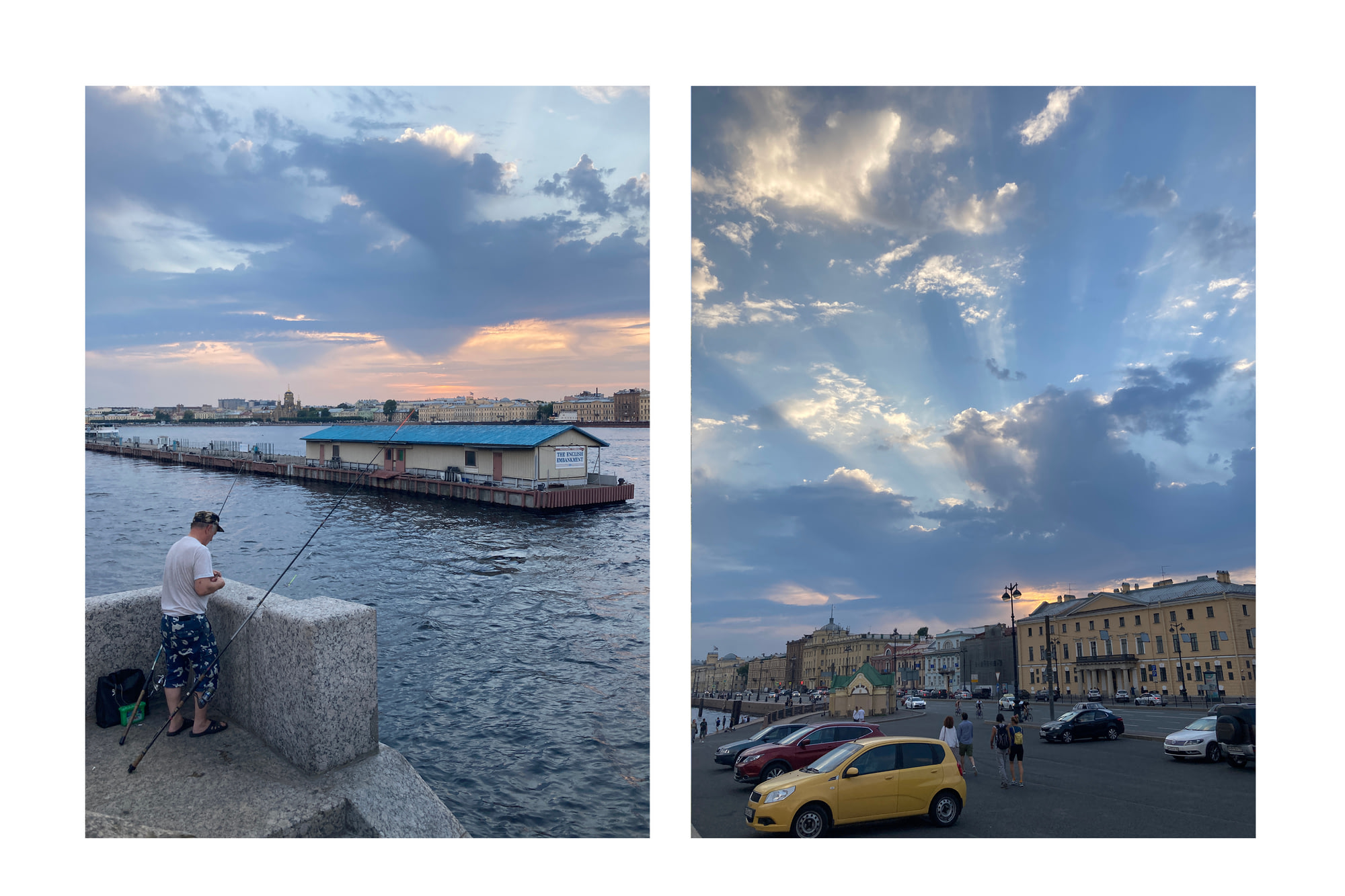

I move on to the city, and it welcomes me with its soft August sky.

Street performers rest under the monument to Peter the Great, the founder of St.Petersburg.

The friend of the golden tsar brought food and drinks, and now they drink.

On the street called Dnipro Alley, someone tagged “NO WAR” on the house wall.

War permeates the air and minds. People talk about it at the cafés, protected by loud music; whisper about it in bookstores. War is rarely called by its name – perhaps for fear of imprisonment for discussing it, perhaps because it is still a painful realization that the country is at war. Instead, you hear euphemisms. “Since you know when,” people say. “Since it all began” or “after the known events”.

In 2003 a memorial stele was erected on the bank of the Neva River, reminding us of things past.

From this embankment, in the autumn of 1922, prominent figures of national philosophy, culture and science went into forced exile.

One hundred years have passed, and here we go again.

The yellow-white General Staff building houses the headquarters of the Western Military District. The “Z” painted on military vehicles of the Russian Armed Forces is believed to indicate that the vehicle belongs to the Zapadnyy voyennyy okrug - Western Military District.

In front of the yellow-white General Staff building, a photo exhibition takes place. Dramatic black and white photographs, taken in 2014, show portraits of children living in the war zone of the Donbass, eastern Ukraine.

Down the street, breakdancers dance to Busta Rhymes.

My brother makes and plays balalaikas. He builds them based on the old designs, and uses self-made leather strings.

And they sound soft and warm.

Soft and warm.

What is not the center of the city has its own atmosphere.

At my sister’s, there is always movement.

Car doors have to be explored and repaired; beds have to be jumped on, tractors and cars drawn.

August in the city is full of heat and chaos.

Sometimes you just have to lie down and rest.

“Glory to Russia’s heroes” billboards are quite visible in the new housing developments.

There is a very specific aesthetic to these places, oscillating between a careless vastness and kitsch.

Signaling safety – canons and cameras.

Signaling wealth – Gazprom Tower, built in 2019, is currently the tallest building in Europe.

Whatever was going on, still goes on.

But you are constantly reminded of the war by billboards, graffiti, and even street signs –

Kherson Street to the left, 3rd Soviet Street to the right.

Everything is close by.

One of the many Georgian cafes serves neon tube khachapuri.

A Jewish cafe on Rubinstein Street still makes the best baba ganoush.

One bar is offering a new craft beer - “На Берлин,” meaning “toward Berlin,” a slogan that was painted on Soviet tanks in World War II.

A Soviet-made tram passes in front of a Volkswagen dealership. Volkswagen has exited Russia after the war started. Soviet-made tram perseveres.

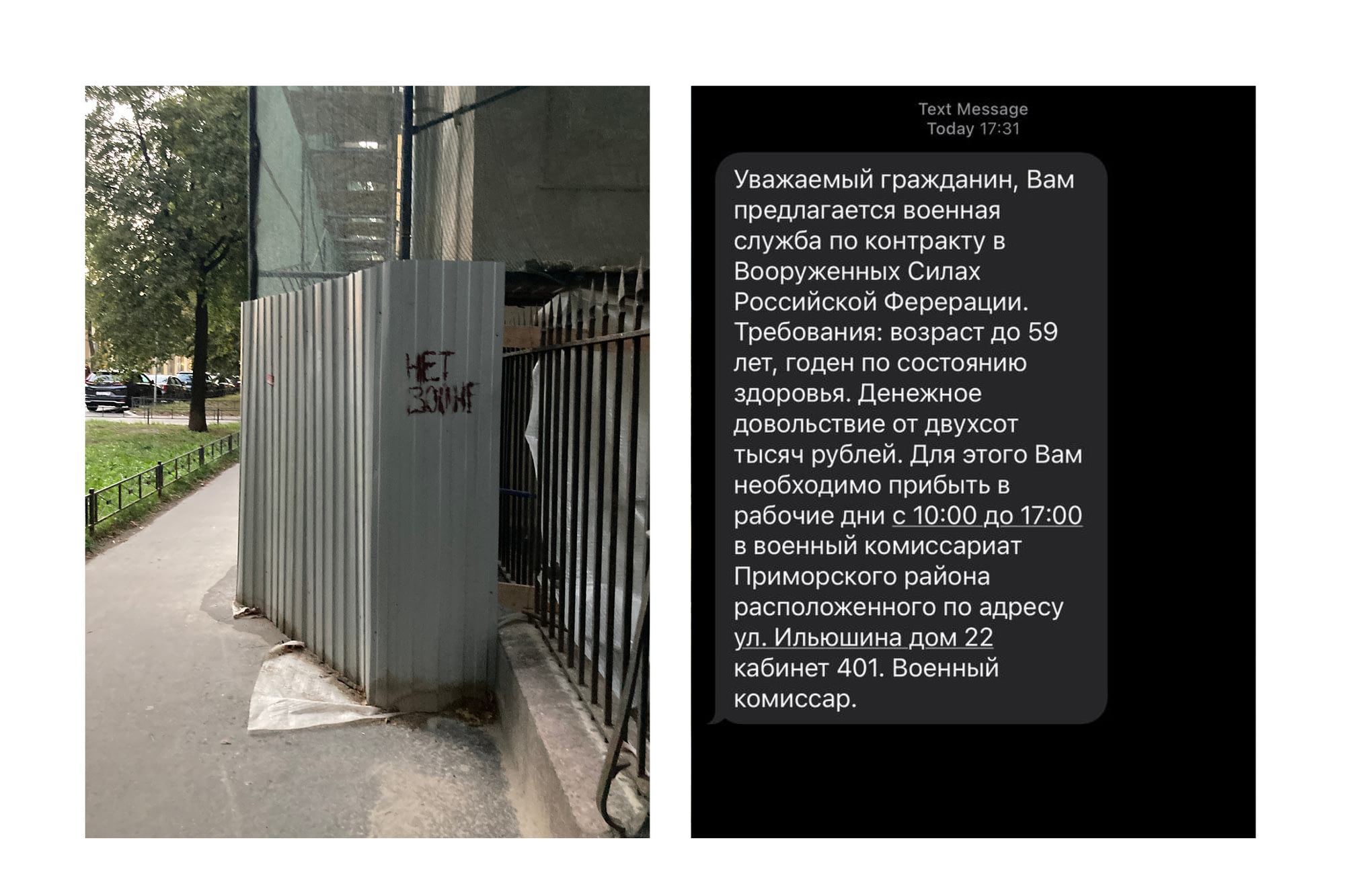

“NO WAR”. Writing it on walls remains one of the last forms of protest.

SMS spam asking you to become a contract soldier in the Russian army. Starting salary of 200 000 rubles (ca. 3300€ at the time), about five times the average salary.

Fearing that SMS spam from the army might be a bad sign, I bought a bus ticket to Helsinki and left the city. Mobilisation was declared a week later.

The cats, however, remained unphased.